To Close Racial Health Inequity Chasm, a Comprehensive Audit of Historical Policies, Events and Practices is Needed

Posted in News Release | Tagged health disparities, health equity, racial disparities, racial justice, Racial Justice Institute, research, School of Nursing & Health Studies

Media Contact

Karen Teber

km463@georgetown.edu

WASHINGTON (February 7, 2022) — A thorough examination of federal as well as local — city, county, and state — historical policies, practices and events is imperative to fully understand why health disparities exist and persist, posits a Georgetown University team of researchers.

Writing in the February 2022 “Racism & Health” issue of Health Affairs, Christopher J. King, PhD, MHSc, FACHE, chair of the Department of Health Systems Administration at Georgetown’s School of Nursing & Health Studies, and his co-authors explore how structural racism and historical events socially, economically and politically disenfranchised Black residents in Washington, DC, yielding stark differences in health outcomes.

Associated Event

To highlight its theme issue, “Racism & Health,” Health Affairs hosts a discussion led by its editor-in-chief, Alan Weil, and Christopher J. King, PhD, MHSc, FACHE, chair of the School of Nursing & Health Studies’ Department of Health Systems Administration, on how structural racism and historical events socially, economically, and politically disenfranchised Black residents in the District of Columbia, yielding stark differences in health outcomes. “Race, Place and Structural Racism: A Review of Health and History in Washington, D.C.” takes place on Monday, February 7, from 6:00 to 8:00 p.m., at Busboys and Poets (450 K St NW).

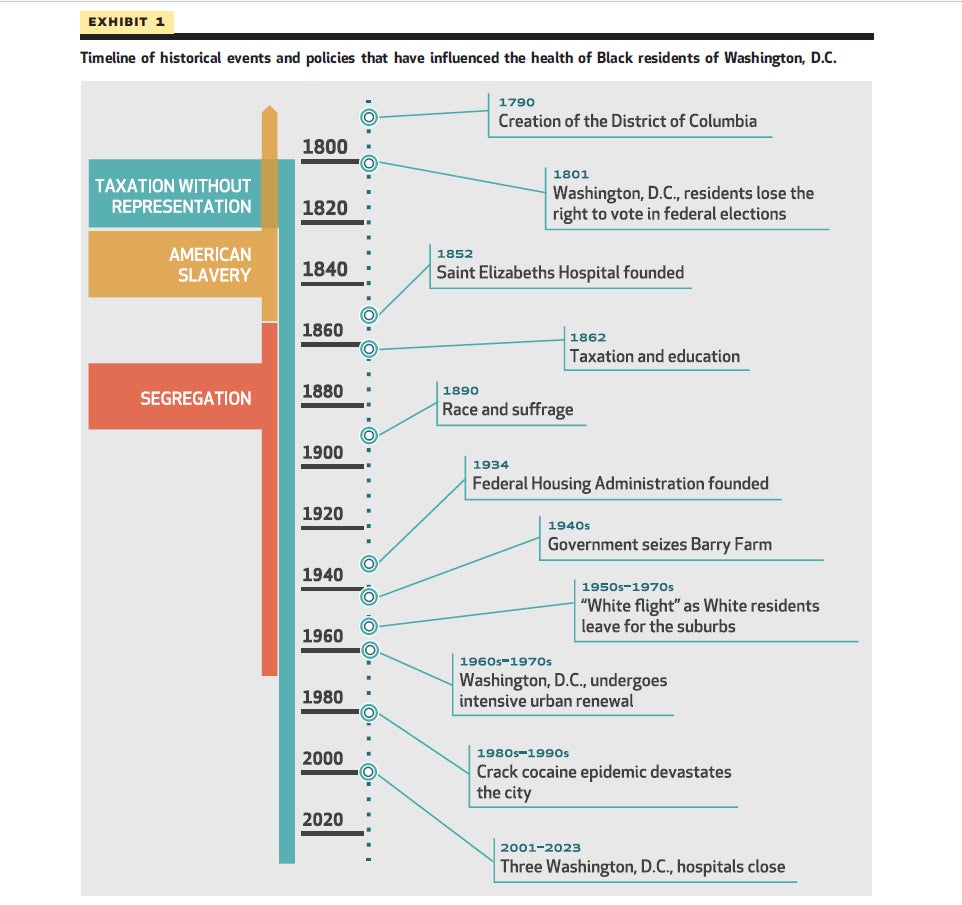

In “Race, Place, and Structural Racism: A Review of Health and History in Washington, DC,” published today, the researchers examine the history of local and federal policies that have disproportionately impacted the health and well-being of Black residents from the District’s founding in 1790 through today.

“Addressing root causes of health disparities will require us to reflect on the past and critically audit contemporary practices that may sustain inequitable conditions by race and place,” says King, a recognized expert on the intersection of race, health and health care. “In our paper, we corroborate this point by sharing data on geographic differences in infant mortality and life expectancy and overlay those findings with racial distribution.”

“Race and racism have played fundamental roles in shaping policies and practices, even when race is not explicitly mentioned in the policy and even if differences by race and place are not intended,” explains senior author Derek M. Griffith, PhD, founding co-director of the Georgetown Racial Justice Institute and professor of health systems administration. “The legacy of policies that are long forgotten continue to have important implications for people’s ability to access resources that we know are critical for health and well-being, including education, housing and food access.”

As with many other cities, Washington, DC, has experienced historic events such as urban renewal and white flight, along with policies such as redlining that have all contributed to racial differences in health outcomes by race and place.

A determinant of health that is unique to Washington, DC, is the lack of autonomy and federal representation that results from its status as a federal district instead of a state.

“We hear often about how statehood would allow DC residents to have a voice at the federal level, but we don’t often discuss how this form of disenfranchisement impacts health,” King explains. “A recent example involves the ongoing pandemic.”

In March 2020, as COVID-19 tightened its grip on the nation, Congress passed a $2 trillion COVID-19 stimulus bill. Initially, Congress withheld more than $755 million in relief from the District than it would have allocated it if it were a state. States with smaller populations than Washington, DC, and state residents that pay less in federal taxes received these resources in their initial allocation. Congress retroactively distributed the money to the District the following year.

King says the delay in federal funding to the District limited access to testing and personal protective equipment in workplace settings, and loss of employment, health insurance or both.

“Because the District didn’t receive federal funding initially as other states did to support recommended mitigation strategies, essential workers — many of whom were people of color — were left vulnerable to infection and susceptible to conditions with long-term implications,” King explains. “The pandemic amplified why so many professional organizations have branded systemic racism as a public health crisis and also serves as a reminder of the impact of inequities in federal funding between states and the District.”

“The slogan ‘taxation without representation’ has become symbolic of entitlements that residents of states enjoy that DC residents do not,” Griffith says. “There is empirical evidence that links political representation and Black-White inequities in infant mortality that is consistent with the patterns of health by race and place that we found in DC.”

King and his colleagues also share the story of Anacostia’s Barry Farm, a vibrant community of Black intellectuals and entrepreneurs, including Frederick Douglass, that emerged after the Civil War. Unsettled by their activism, many white residents expressed disdain with the flourishing community of landowners. Ultimately, the community was destroyed in the early 1940s when the government demolished homes and businesses and discontinued maintenance services in sections of the community. An eminent domain action allowed for the construction of public housing and Suitland Parkway.

“An entire generation of Barry Farm residents were stripped of the ability to accumulate wealth, and the loss of assets that would have been passed on to family members over time,” King explains.

“It is no accident that maps of the percentage of Black residents, poor health, lack of schooling, unemployment, food insecurity and poor housing have consistently shown the same people and places in the District struggling,” says Griffith. “To remedy these patterns, we have to create policies that begin from the recognition that current patterns of health by race and place cannot be separated from who historically and currently has power to make and enforce policy decisions.”

King wants this type of historical analyses to inspire policymakers and practitioners in communities across the nation to conduct similar examinations in their efforts to create and evaluate policies to achieve racial justice.

“We don’t know all the answers,” he says, “but if we are humble and willing to learn the history and the consequences of trauma endured for generations, we can correct harmful actions and move closer to creating equitable conditions that will close the chasm.”

In addition to King and Griffith, the authors include Bryan O Buckley, DrPH, MPH, adjunct assistant professor at Georgetown and a research fellow at MedStar Health’s Institute for Quality and Safety; and Riya Maheshwari, a Georgetown University undergraduate student.