Zebrafish Research Strengthens Students’ Interest in STEM

Posted in GUMC Stories | Tagged biomedical research, community outreach, education, STEM, zebrafish

(April 26, 2019) — Participating in high-impact studies, peering into a fluorescence microscope and tracking cancer cells in animal models are all things Eric Glasgow, PhD, never had an opportunity to do when he was in college, much less high school.

“Even though I always knew I wanted to be a scientist, I was barely even an average student,” admitted Glasgow, who is now a molecular biologist and an assistant professor of oncology at Georgetown University Medical Center. “Internships and other work placement experiences were also not as commonplace as they are now,” he explained.

This only motivated Glasgow to provide these experiences for dozens of trainees over the years, including for high school students, whom he believes benefit immensely from such early exposure.

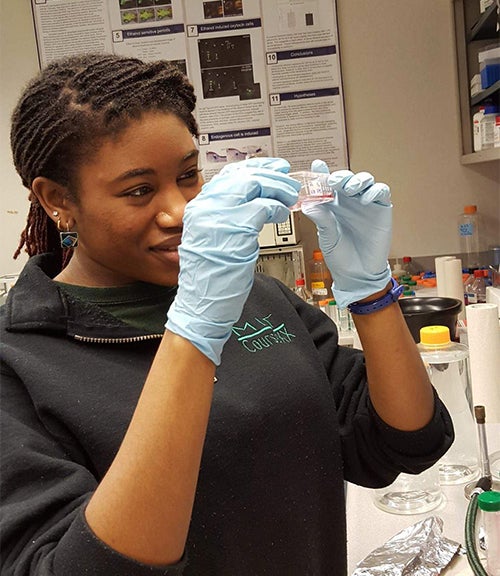

As the director of Georgetown’s Zebrafish Shared Resource and a leading expert in the use of zebrafish as a model for studying human disease, Glasgow is not only a highly cited scholar, but has also become an educator and mentor to local high school students, including several who have gone on to study at prestigious universities.

“It’s the right thing to do for both these students and for society as a whole,” he said. “I feel I have something to contribute.”

An Emerging Research Model

Traditionally, mice and rats have been the model for biomedical investigations, but they are increasingly being replaced or supplemented by studies with zebrafish. As vertebrates, zebrafish have many of the same organ systems as humans and are able to regrow these organs, a process known as organ regeneration. Moreover, because they reproduce in such large numbers, zebrafish research is more cost-effective than working with mice

Another benefit to working with zebrafish? “It’s fun,” Glasgow said.

“Zebrafish are so exciting because you can see them, the entire organ system — and their heart beating and blood circulating,” he said. “You can see results of experiments more clearly. It sort of gives students some immediate feedback.”

The aquatic creatures are now being used to study cancer treatments and many other areas of human disease.

An Early Exposure to Zebrafish Sparks Career Focus

Years before he started working with zebrafish, Glasgow was a child fascinated by dinosaurs — at one time he thought he would become a zoologist. His journey began to take shape when he started taking classes in the natural sciences as a student at California State University, Northridge.

His first time working with zebrafish came during graduate school at the State University of New York at Stony Brook. It was the mid-1980s, and he had been studying optic nerve regeneration in goldfish. “It was around this time that some of the first big papers on this topic came out,” Glasgow said.

Seymour Benzer, PhD, a pioneer in molecular and behavioral genetics, visited his school to give a seminar and stopped by a lab in which Glasgow had been working. When someone mentioned the goldfish studies to Benzer, Glasgow remembers him saying, “Zebrafish, you can do genetics with zebrafish!”

Almost immediately afterward, Glasgow went to the pet store and bought some zebrafish, bred them and put them under microscope. “I stayed up for two days. I was fascinated and amazed by their development,” recalled Glasgow, who has been studying them since then.

Aesthetics of Zebrafish Accelerate Scientific Engagement

Over the last decade, the high school students who have interned in Glasgow’s lab have come from Sidwell Friends School, The Madeira School, National Cathedral School, St. Albans School and Montgomery Blair High School.

Part of what keeps them so engaged is the hands-on, visual and aquatic nature of the work.

“I find zebrafish so fascinating because of the genetic similarities but structural differences they have with humans,” said Kathryn Fronabarger, a senior at The Madeira School in McLean, Va., who recently spent five weeks interning with Glasgow. “Because Dr. Glasgow’s lab could work with hundreds of embryos at a time, the process was very data-filled and rewarding.”

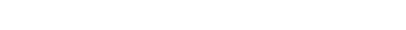

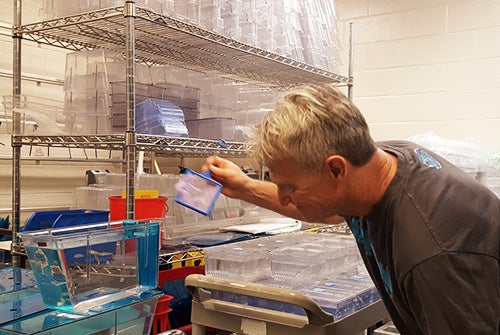

Now pursuing a PhD in materials science at Northwestern University, Chamille Lescott started working in Glasgow’s lab as a freshman at Sidwell Friends School. Impressing Glasgow early on, Lescott devised and proposed an experiment of her own that tested her hypothesis on pigmentation development and pattern formation for the embryos.

As a senior, Lescott was first author on a research poster with Glasgow, which she presented at the 10th Annual International Conference on Zebrafish Development and Genetics.

“Zebrafish are a beautiful model organism,” she said. “Looking into a microscope and seeing a tiny embryo developing fills me with joy and excitement every time.”

Building Confidence in Future Scientists

On a student’s first day in his lab, Glasgow demonstrates how to care for and transfer zebrafish embryos. After that is mastered, they can move on to more advanced projects, like assisting with permutation tests in support of ongoing studies.

While some high school students have experience being in a laboratory setting, it’s a completely unfamiliar environment for others. “Once they work here for a while, they start to develop some familiarity, especially as they’re getting to see how it works on a day-to-day basis,” Glasgow said.

Lescott remembered Glasgow creating and maintaining a welcoming environment in the lab for her and other high school students. “All of the Glasgow lab students enjoyed their time there,” she said. “I remember laughing every day.”

Once Fronabarger became comfortable with both the physical environment and the lab staff, she began critically thinking about her assigned projects. By the time her internship in Glasgow’s lab concluded, she was using a high-content imaging computer to capture fluorescent images of tumors — a task that took much practice and observation before she could get it completely right.

“At first, I was intimidated by the capabilities that highly specified technology gives the lab staff,” said Fronabarger, who will be attending Tulane University in fall 2019. “But Dr. Glasgow is a pioneer for hands-on learning, and by giving his interns the ability to try the process out for themselves and ask questions, he was able to create an environment that is friendly to trial and error.”

“He has been a consistent mentor and friend over the years,” Lescott added. “I would not be pursuing my current career path without his influence.”

Seren Snow

GUMC Communications