Training Programs Emphasize Mentoring for Biomedical Graduate Students

Posted in GUMC Stories | Tagged Biomedical Graduate Education, biomedical research

(September 21, 2018) — For decades, the tumor biology (TBIO) and neural injury and plasticity (NIP) programs at Georgetown University Medical Center have educated the next generation of biomedical researchers with funding from NIH T32 grants, which support pre- and post-doctoral research training.

Both programs focus on mentoring students to help them achieve their goals.

“The glue that keeps the program together is that 33 of the 100 faculty members at Georgetown Lombardi participate in this program,” says Anna Riegel, PhD, the director of the program.

As the director of the NIP program, Kathleen Maguire-Zeiss, PhD, agrees. “NIP is only as successful as the funded mentoring faculty,” she says.

Individualized education

The TBIO program is one of the longest running and longest continually funded pre- and post-doctoral NCI-funded training programs in the country, says Riegel, who has just completed the application for another five years of program funding. Until recently, Riegel also served as director of graduate studies at Georgetown Lombardi.

In addition to Georgetown Lombardi faculty, Riegel says that faculty members from other Georgetown departments mentor TBIO students. The emphasis on mentoring is important to the program’s participants, including Max Harley Kushner (G’19).

“I can’t speak highly enough of the Georgetown TBIO program,” says Kushner, a fourth year TBIO doctoral candidate. “The researchers span diverse focus areas, and the resources and ranges of experiences are wide. There are many opportunities to explore new research areas, collaborate on projects and pave an individualized PhD training process with your mentor and thesis committee.”

While more than 100 alumni have participated in the TBIO program over its 23-year history, it only accepts six or seven applicants annually, Riegel says. The size of the program was also important to Kushner, who is studying the interaction of proteins that bind to DNA and promote development and progression of breast cancer. “The program is small enough to intimately know the research, researchers and the department, yet large enough to have a variety of focus areas and expertise,” he says.

Clinical perspective on basic science

The advanced predoctoral NIP program, which is funded through 2022, consists of students and faculty members whose research is focused on neural injury and recovery. To date, every one of the program’s alumni have earned their doctorates and are now contributing to the future of neuroscience.

“That statistic is unusual, and one way we measure the success of this training program,” says Maguire-Zeiss, who is also co-director of the Center for Neural Injury and Recovery at Georgetown and director of the Interdisciplinary Program in Neuroscience (IPN).

Another unusual attribute of the NIP program is that students learn to view their basic science research through the clinical lens by shadowing physicians at the National Rehabilitation Hospital to observe patients undergoing therapy after stroke or traumatic central nervous system injury. They also work with doctors who treat movement disorders and observe neurosurgeons in the operating room as well as post-surgical debriefings. In monthly meetings, the trainees share their experiences with each other.

“It’s a real strength of our neuroscience training program, offering meaningful clinical experiences and time for reflection,” Maguire-Zeiss says.

Cameron McKay, a doctoral candidate in the IPN, says that the NIP program has given him “a specific focus on basic science and clinical perspectives on neural injury and plasticity.” The program encouraged him to expand his research from focusing on how children with dyslexia respond to reading intervention to also looking at how children with dyscalculia, a developmental disability in math skills, respond to math intervention.

“NIP has fostered my growth as a researcher and independent thinker. The students and faculty in the program come from various backgrounds and departments, from neuroscience and biology to pharmacology and biochemistry,” he says. “This interdisciplinary and collaborative environment has allowed me to view and interpret my research, which studies human participants, in the context of the cellular and molecular mechanisms of plasticity.”

Adapting to changing fields

Both Maguire-Zeiss and Riegel say that their programs adapt as science and medicine progresses.

“When I started, no one cared about immunology. We didn’t think it played a big role in cancer and therapy,” says Riegel. “Now that has completely changed, and I am learning as much from fellow faculty as the students are. In fact, to keep up, we are de-emphasizing didactic lecture classes in favor of flipped classrooms and discussion.”

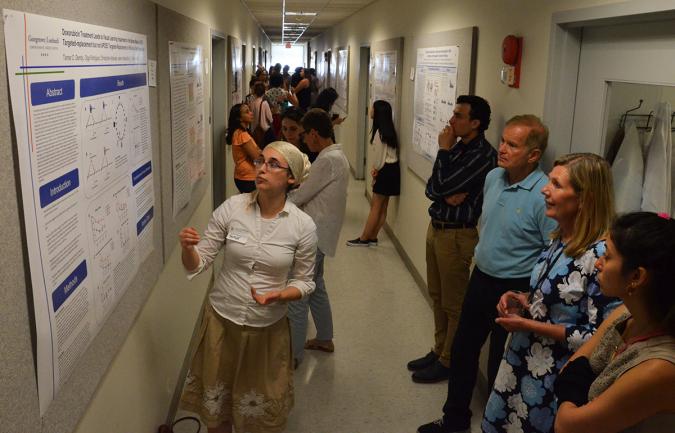

One way that the TBIO students learn from each other is by organizing an annual research retreat, something they have done for the last five years. The July 20 retreat included 50 PhD students and postdocs, as well as Georgetown Lombardi faculty and staff. Kushner, Roth and fellow student David Zahavi organized the retreat, which included research posters from Georgetown Lombardi scientists and students, an alumni panel, a scientific workshop and an “individual development plan” session.

In the NIP program, trainees choose a seminar speaker and host them for a visit, which gives them the opportunity to plan an itinerary, share their data, and build relationships with the wider scientific community. “These trainees also choose the topics for our monthly NIP meetings — this independence really keeps them invested in science,” says Maguire-Zeiss.

Renee Twombly

GUMC Communications