Georgetown Students Strive to Reduce Opioid Overdose Deaths in DC

Posted in GUMC Stories | Tagged community outreach, cura personalis, HOYA Clinic, opioid epidemic, opioids, School of Medicine

(January 2, 2020) — Many communities are struggling to stop the opioid epidemic, and the District of Columbia is no exception. According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), there were 244 overdose deaths involving opioids in DC in 2017, or 34.7 deaths per 100,000 persons. Compared to the national average of 14.6 deaths per 100,000 persons, DC had the third-highest rate of opioid-involved overdose deaths in the country.

Motivated to make a difference in DC, Jack Pollack (M’20) developed the Hoya Drug Overdose Prevention & Education (DOPE) Project with classmates Mary-Kate Mekhail (M’20), Kaitlin O’Sullivan (M’20) and Erica Meninno (M’20), a two-step strategy to address the problem by creating an independent student group to work with local community organizations and preparing future physicians to care for patients with opioid use disorder.

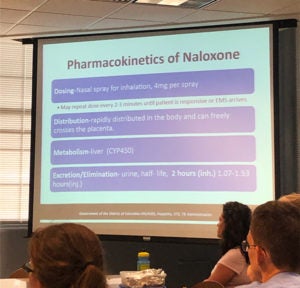

Together, they set out to train groups of medical students to educate DC community members who are at highest risk of experiencing or witnessing opioid overdose. They also explain how to recognize the signs of an overdose and safely intervene with the lifesaving opioid overdose antidote naloxone, marketed as NARCAN.

“We were lucky enough to have the support of Dr. Eileen Moore, one of the medical directors at the HOYA Clinic, and through her, we worked closely with Dr. Adam Visconti in the Department of Health, a Georgetown family medicine graduate,” says Meninno, a Hoya DOPE leader.

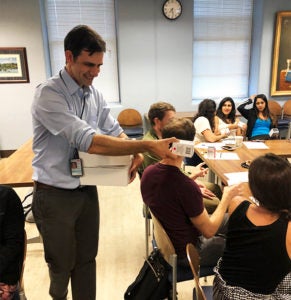

“The Department of Health began to train our volunteers and provide free NARCAN that we could use at distributions,” Pollack says. “As a result, over the last few months our volunteers have been able to distribute hundreds of NARCAN kits free of charge.”

Leading Community Education to Reduce Overdoses

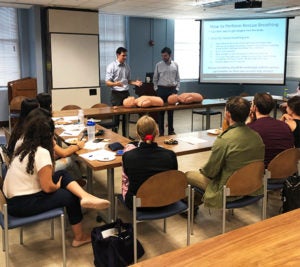

Following training, Hoya DOPE volunteers partnered with community sites throughout the District of Columbia to set up education sessions. These sessions take half an hour and usually begin with information on the opioid epidemic nationally and in the DC area. Student trainers have reported that due to attendees’ varying levels of knowledge on the topic, each session is usually adjusted to accommodate audience needs and related questions.

“We talk about how to recognize the signs or symptoms of an opioid overdose,” Meninno says. “We often emphasize the difference between someone who is ‘high’ versus someone who has overdosed, because sometimes that’s a common question you get from a lot of people. It’s like, ‘How do you know when someone is truly in danger of dying from an overdose?’”

Community attendees say that the most important aspect of these sessions is the hands-on practical element. “We provide a ‘step by step’ on how to administer naloxone,” Meninno says. “It’s really a simple process, so we walk people through that. We have a little trainer naloxone nasal spray with us so that people really feel comfortable with the mechanism of it.”

To date, training sessions have been delivered in an array of community settings, including churches, Anchor Behavioral Health and multiple DC Coalition for the Homeless transitional housing programs.

“During one of our first distribution events at a church in the community, one participant said to me, ‘I’m sorry for asking so many questions. It’s just that my son uses, and I want to make sure I know exactly what to do if he overdoses,’” Pollack says. “After all the time spent developing this program, handing naloxone to this father was one of my proudest moments of medical school.”

Planning for a Cultural Shift

As the need for these community education sessions grows, Meninno is confident that students can meet the demand. “We now have over 70 students across all four classes at Georgetown University School of Medicine (GUSOM) trained by the Department of Health as formal Hoya DOPE project volunteers,” she says.

A succession plan is in place once this year’s students graduate in the spring. The project’s leadership and planning responsibilities will be passed to a few students from the classes of 2022 and 2023 in order to continue this innovative and important work.

Looking to the future doesn’t stop there. As a result of the rising rate of opioid use disorder and the growing number of overdoses, new training modules have been added into the GUSOM curriculum.

“We are very proud of GUSOM for including modules into the formal curriculum on substance use disorder and treatment, as well as the most recent addition of buprenorphine x-waiver prescriber training,” says Meninno, describing the sessions physicians must complete to prescribe buprenorphine, an opioid use disorder treatment.

“Most medical students don’t get the opportunity to complete this training while still at medical school,” Meninno says. “As a part of this, the importance of prescribing naloxone alongside opioid prescriptions is emphasized, which is a simple and an extremely important cultural shift we can make in medicine to reduce the risk of overdose deaths.”

“As a volunteer, this project gives you the chance to go out into DC and empower people with a tool that saves lives,” Pollack says. “What could be a better study break than that?”

For more information on Hoya DOPE, email hoya.dope.project@gmail.com.