Georgetown Neuroscience Student Networks with Nobel Laureates at Annual Meeting

Posted in GUMC Stories | Tagged biomedical research, School of Medicine

(July 26, 2018) — After a 20-mile bike ride near the Alps this June, Patrick Malone, a student in the MD/PhD program (G’19, M’21), found himself at the intersection of Germany, Switzerland and Austria. It was a refreshing break from the purpose of his trip — networking with some of the most incredible minds in science.

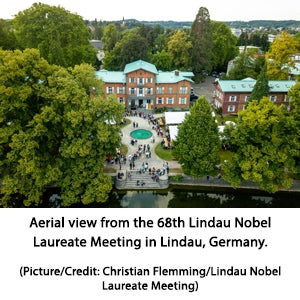

With 39 Nobel laureates and 600 young scientists from 84 countries in attendance, the 68th Lindau Nobel Laureate Meeting in Lindau, Germany, was in full swing.

Malone was one of 29 students from the United States selected to attend the weeklong event due to his research in neuroscience and speech perception.

He was in good company, attending panel sessions, poster presentations and discussions with young scientists from around the world.

“Students come from literally all over, and hearing their perspectives, what they’re working on and how science is done differently internationally, was pretty awesome,” said Malone.

‘The Brain Tells You Its Secrets and Then You Follow the Leads From There’

For his thesis research, Malone is exploring how the brain can learn to perceive speech through the sense of touch.

Together with his mentor, Max Riesenhuber, PhD, and in collaboration with Lynne Bernstein, PhD, at George Washington University, Malone is training normal-hearing individuals to use a vibrotactile speech prosthesis, a sensory substitution device that converts auditory speech into patterns of vibration on the skin.

“One question we have is this: When people learn to perceive speech via touch, do they learn it in a way that interfaces with the existing auditory speech system in the brain, or is there an entirely new ‘vibrotactile speech’ neural system built up?” Malone said.

“It’s interesting because despite decades of research and development with vibrotactile speech aids, no one has actually done neuroimaging experiments to figure out how your brain learns this stuff.”

Malone is using advanced neuroimaging techniques to study how the brain perceives speech through touch because he hopes this research will lead to more effective devices for those who suffer from partial or total hearing loss.

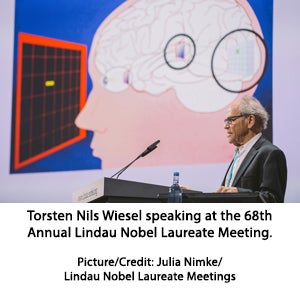

At the meeting, Malone was able to delve deeper into neuroimaging when he was given the unique opportunity to have lunch with Swedish neurophysiologist and 1981 Nobel Prize winner Torsten Nils Wiesel, MD.

“I got to ask him everything I could possibly think of. He had a lot of technical insights that were interesting, but the main question I asked him was whether the state of neuroscience was where he thought it would be in 2018.”

Malone was also able to glean inspiring insights from Wiesel’s life and work. During his talk titled “Exploration of the Visual Cortex,” Wiesel shared his approach to experimentation and research.

“When he and [David Hubel] did their experiments, they didn’t have a hypothesis. They did it in a totally data-driven way,” Malone said.

“The expression [Wiesel] used repeatedly was: ‘The brain tells you its secrets and then you follow the leads from there.’ They didn’t have a pre-planned idea of what they were going to look for — they let their discoveries guide where they would look next.”

Getting Back to Basics

Hearing from Nobel laureates like Wiesel reminded Malone that while technology is an important tool, methodology is also critical for scientific discovery.

“At the Lindau conference, many of these scientists won Nobel prizes close to 30 years ago,” he said. “These discoveries are truly paradigm-shifting discoveries in their respective fields, but they weren’t done with special computational methods. They seemed more grounded in the methodology that they used.”

The meeting also renewed Malone’s dedication to pursuing his goals.

“It’s important not to lose sight of what your ultimate goal is. When you’re a nerd like me, it’s easy to get lost in the latest computational tools for analyzing data in the brain,” he said.

“However, the ultimate goal is to understand how the brain works and to use that understanding to help those who suffer from neurological and mental disorders.”

Giuliana Cortese

GUMC Communications