Biomedical Graduate Student Advocates for More Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing Scientists

Posted in GUMC Stories | Tagged Biomedical Graduate Education, deaf and hard of hearing, disability awareness

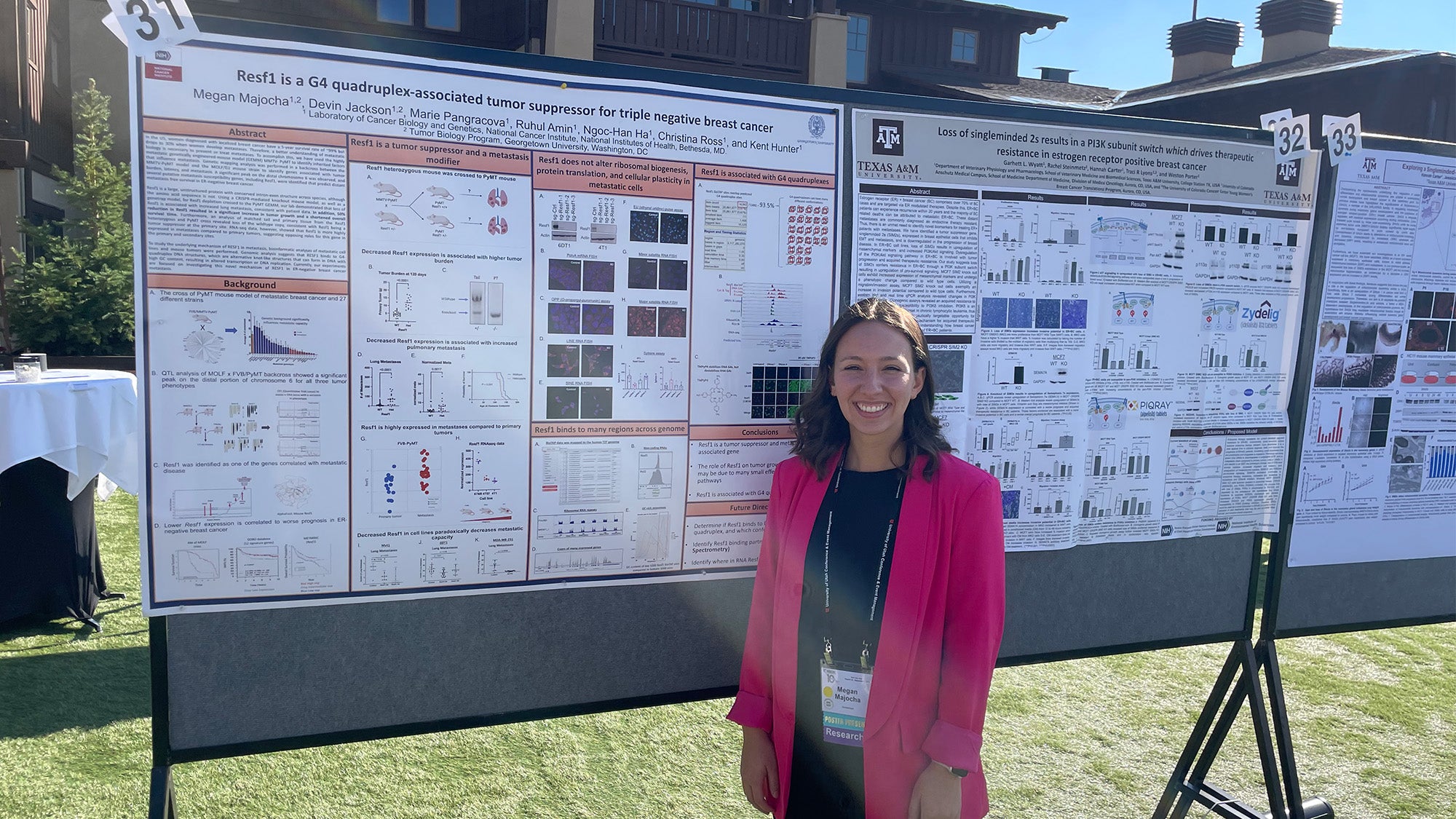

(October 27, 2023) — Megan Majocha (G’24) finds herself on a dual mission. As a PhD student conducting breast cancer research, she wants to contribute to the understanding of what drives a specific type of cancer to spread. But as a scientist in the making, Majocha, who is deaf, also wants to make sure the path to becoming a researcher is smoother for kids who grew up just like her.

Majocha, a PhD candidate in tumor biology, knew from a young age she wanted to be a scientist, but did not know of a deaf scientist until she entered college as an undergraduate at Gallaudet University, a higher education institution in which all programs and services are specifically designed for students who are deaf and hard of hearing (DHH).

According to the National Science Foundation, only 1.2% of doctoral degrees conferred annually in the United States go to DHH students, a statistic that falls way short of being representative of the Deaf community.

Majocha said barriers such as a lack of robust translation services can discourage deaf people from pursuing careers in science.

“To become a scientist as a hearing individual, you already have to have tenacity and persistence to overcome so much, but it just becomes that much harder when there’s a communication barrier,” she said.

Since starting her studies in 2019 at Georgetown through the National Institutes of Health (NIH)-Georgetown partnership program, Majocha has consistently advocated for greater accessibility, including interpretation and transcription services for classrooms. She has also inspired greater understanding from faculty and fellow students about the use of interpreters, such as speaking one at a time rather than in overlapping conversations during discussions.

‘I Don’t Have to Fight To Be Heard’

Majocha is a fifth-year doctoral student studying one specific protein that contributes to the metastatic progression of triple-negative breast cancer in the lab of Kent W. Hunter, PhD, at NIH. She is from a third-generation deaf family outside of Pittsburgh, where she grew up fascinated by science, especially biology.

She first joined Hunter’s lab at NIH as a post-baccalaureate, where she learned about the NIH-Georgetown program in tumor biology from colleagues. For the first two years of the program, Majocha took courses and completed her lab work at Georgetown.

“Although I applied to several programs, I was interested in the NIH-Georgetown program because I love the Deaf community here in DC and because NIH has such great accessibility resources,” said Majocha. “NIH provides top-quality STEM interpreters that are easy to access on demand and are qualified to speak to the level of my research.”

Majocha credits the NIH interpreters as the primary reason she pursued her education and research in the NIH-Georgetown program.

“Here, I don’t have to fight to be heard,” she said.

Learning To Be an Advocate in the Classroom

Starting classes at Georgetown in 2019 came with many challenges for Majocha.

“Many of my graduate courses were audiotaped and shared with the class, which wasn’t helpful to me as a deaf student,” said Majocha, who would still require an interpreter to access the audio.

“So instead of being able to just do the coursework, I ended up having to schedule meetings with support services and professors,” she said. “I advocated for myself that I be provided transcripts of the audio so that I could revisit the class material like the rest of my cohort.”

The transcripts were important for Majocha because they provided an opportunity to learn the material in scientific English instead of American Sign Language (ASL). “I prefer to read and review material in scientific English,” Majocha said. “ASL signs can vary and there’s not a lot of scientific interpreters.”

But translating concepts between ASL and English can be difficult, and sometimes concepts can get lost in translation.

“It can be difficult going between ASL and English,” said Majocha. “I remember an essay question from an exam where I knew how to answer the question with a specific concept in ASL, but I had to write my response in English and I was unsure what words to use.”

As a scientist, Majocha said that she wishes to communicate through publications and presentations in the preferred English language format of her field but realizes this may result in members of the Deaf community who prefer communicating in ASL not grasping the full scope of her work.

Keep Talking, Keep Growing

Communication is not only essential for learning, but also for advancing Majocha’s research and connecting with colleagues.

“After exams, we would be out celebrating, and although my classmates tried very hard to include me, the communication barrier between us felt isolating,” Majocha said.

Majocha realized that in order to be successful at Georgetown while she completed her coursework, she would need interpreters available constantly throughout the week, including for more informal exchanges.

“I also did not want different interpreters assigned to me each day who would be unfamiliar with my coursework and research,” she said. “I was fortunate to have a team of interpreters who picked up the sciences and became super familiar with my research and allowed me to focus on my work.”

In the NIH lab where Majocha is completing her dissertation, she is joined not only by a team of interpreters but also deaf colleagues and her own principal investigator (PI), who is learning ASL.

“Being in a setting where I can chat in ASL makes the communication much more efficient,” said Majocha. “We still may have to call in an interpreter to help talk through deep concepts, but we’re still able to have fluid conversations about our work.”

As she enters the final few months of the NIH-Georgetown program, Majocha reflects on what more needs to be done to ensure DHH students are given equal access to information, and therefore, more equal opportunities for graduate study in the sciences.

Majocha said she hopes that one day universities will easily provide all the resources needed for deaf students and provide training to professors on how to use the resources.

With additional resources, Majocha hopes that more DHH students will pursue careers in the sciences and become the role models for younger generations that she never had growing up.

“I really hope our numbers will grow,” said Majocha.

Heather Wilpone-Welborn

GUMC Communications