Documenting Human Rights Abuses Against Rohingya Refugees

Posted in GUMC Stories | Tagged global health, refugee health

January 21, 2018 — Rohingya refugees faced land mines, starvation, sexual violence and more when they fled Burma, Ranit Mishori, MD, MHS, FAAFP, learned from refugees, humanitarian workers and health workers at refugee camps in Bangladesh. Mishori, professor of family medicine at Georgetown University School of Medicine, spoke to students January 11 about her journey to southeast Asia on behalf of Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) last November.

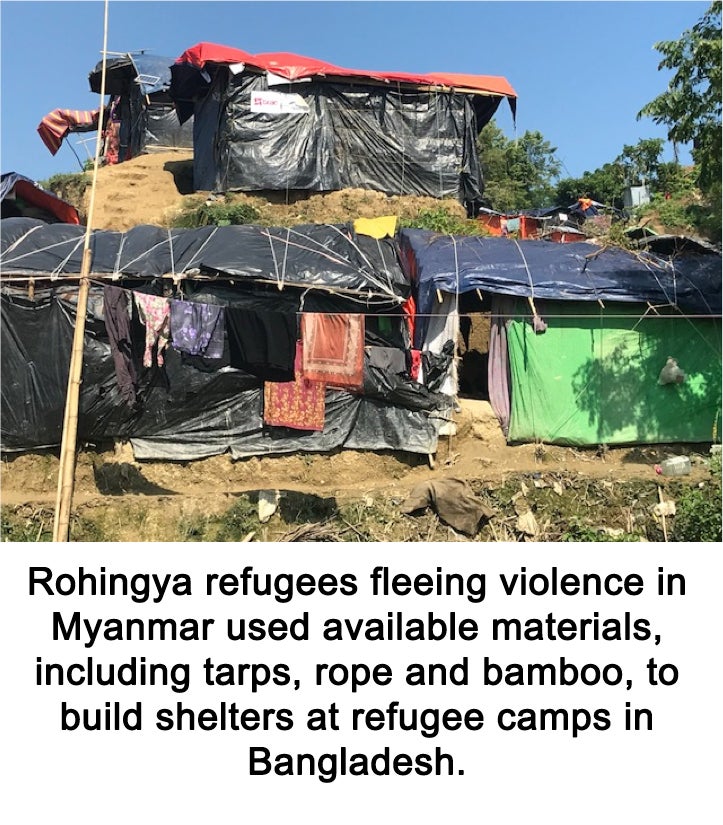

Since August, more than 600,000 Rohingya refugees have crossed the border into Bangladesh and settled in refugee camps, including one camp where 300,000 refugees settled in less than three weeks. Mishori has previously traveled to refugee camps in the Middle East, Rwanda and Kenya, but even she was surprised by the scale of the camps in Bangladesh.

“It’s unbelievably huge and overwhelming, even if you’ve seen refugee camps in the past like I have,” she said at the talk, hosted by the School of Medicine chapter of Physicians for Human Rights.

The mass exodus was prompted by the destruction of Rohingya villages by the Burmese army in response to an attack by Rohingya militants this summer. “We’re talking about dozens of villages that have been completely flattened and burnt to the ground,” Mishori said. “Villages upon villages had to flee across the water into Bangladesh.”

“The most persecuted minority in the world”

Even before their villages were attacked this summer, the Rohingya were struggling in Myanmar. A lot of Rohingya children in the refugee camps “are already malnourished because of discrimination in Rakhine State,” Mishori said.

A Muslim minority from western Burma, the Rohingya people are very devout and have faced years of discrimination and human rights abuses based on their religion. “They’re often called the most persecuted minority in the world,” Mishori said. “They’re not considered human beings even, in some parts of Myanmar.”

As a stateless people, the Rohingya “have no judicial recourse in any country, not in Bangladesh, not in Myanmar. So the only way their leaders can do anything is by speaking to the international community,” Mishori said, underscoring the importance of her work with PHR.

“Who is not there?”

Mishori, a medical expert consultant for PHR, was asked to go to Bangladesh with two human rights experts for about a week to help lay the groundwork for efforts to document atrocities against Rohingya, in order to seek justice on behalf of the Rohingya. “We want to be scientific at PHR. We want to get scientific data,” she said. “You want to have evidence, you want to take pictures, you want to take measurements.”

However, collecting data on the experiences of refugees is extremely challenging. For example, when surveying a population, researchers strive to collect data from a sample that is representative of the entire group. In a refugee camp with 300,000 people, those on the edges of the camp are interviewed more often than those living in the middle of the camp, even though their experiences may not be representative.

To address challenges like that, Mishori sought out the local leaders in the refugee camps. “The first thing you do when you get there is make friends,” she said. “Who is the local imam? Who is the local midwife? Who are the community health workers? The first day, you want to talk to those people.”

In addition to documenting the survivors’ stories, Mishori said, it’s important to consider who it is that researchers aren’t reaching. “The question we kept asking is who is not there?” she said. “Who is not there tells us something about what happened back home.”

Sharing Survivors’ Stories

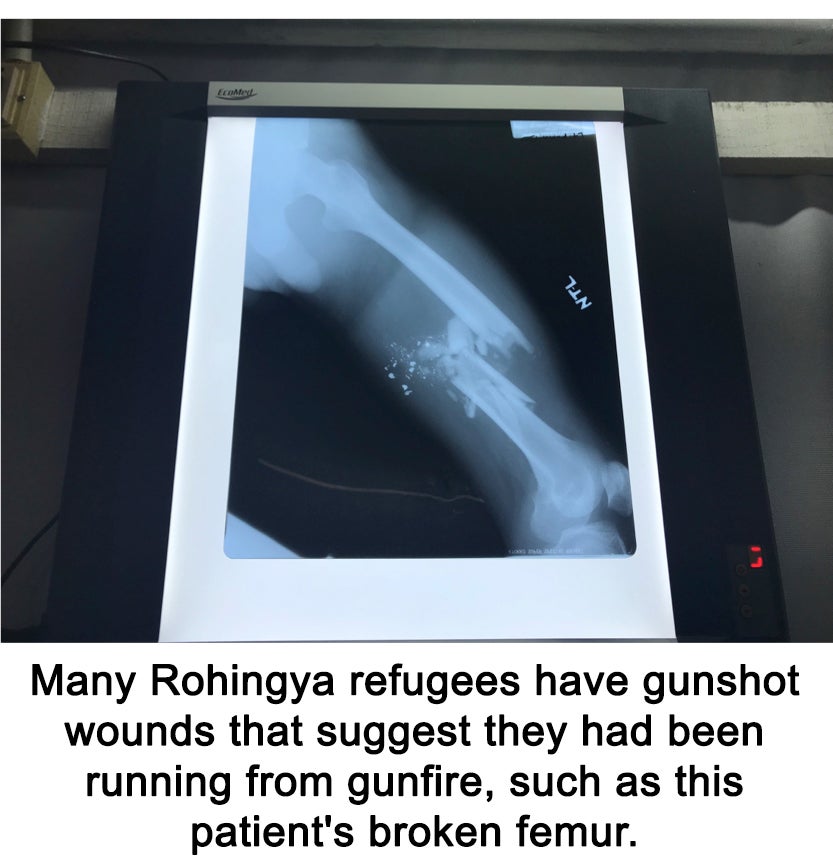

In conversations with refugees, community leaders and health professionals, Mishori heard what refugees endured and saw the injuries that they sustained as they fled. “A lot of people were hit by interpersonnel landmines fleeing the border,” she said, explaining that those specific devices are intended to inflict serious injuries but not death. “It’s for the specific purpose of maiming people.”

Doctors have treated patients with amputated gangrenous wounds and gunshot wounds in their backs, suggesting they were running from gunfire. Refugees also reported high incidence of sexual violence. “Many women experienced sexual violence, or had a family member, or daughter who had,” Mishori said. “There were multiple reports of gang rapes.”

One Rohingya woman Mishori met had arrived at the refugee camp with seven small children after her husband, her sister and her sister’s husband were all killed by the Burmese army. “They’re incredibly malnourished and also traumatized,” Mishori said. Moreover, the woman can’t leave the children behind to stand in line for food, compounding their hardship.

Sharing traumatic experiences can be enormously stressful for the refugees Mishori met. “There is an issue of retraumatization,” she said. “Just retelling the story can retraumatize an already traumatized person,” so taking a history must be done with extreme caution. By working with PHR to collect and document evidence of crimes against the Rohingya, Mishori and her colleagues are hoping to put together a comprehensive report and share it with international organizations, governments and other stakeholder to try to seek justice for the Rohingya and change the status quo.

Kat Zambon

GUMC Communications