Perfectionism Among the Issues Addressed as Medical Students Link Identity and Wellness

Posted in GUMC Stories | Tagged diversity, School of Medicine, student wellness

(April 12, 2019) – Perfectionism, imposter syndrome and isolation were the core themes explored this year at I, Too, Am Georgetown Medicine, as dozens gathered for the annual event created to encourage students to engage in candid dialogues about the identity-driven interpersonal and structural challenges that may arise in their lives on a daily basis.

Students were there to learn from each other and from keynote speaker Elisabeth Poorman, MD, a primary care physician who has written and spoken extensively about wellness among health providers. The event was held April 3 at Georgetown University School of Medicine.

This year’s emphasis was on wellness and included intimate group sessions, each serving as a nonjudgmental, welcoming environment for students to gain a deeper understanding of how their individual experiences shape their approach to the complexities of being a medical professional and the wellness issues that sometimes result.

Embracing Vulnerability

“These white coats often make it seem as if we’re putting on a superhero cape and covering up all of our vulnerabilities,” said Poorman.

She outlined three risk factors for depression in medical school — perfectionism, imposter syndrome and isolation — which she explained have come up countless times both in her research and in conversations with medical students around the country.

Many students acknowledged that it’s the standards they set for themselves, often even before they set foot in their first medical school lecture, that create the confines by which pride in their respective identities can either be stretched to the breaking point or kept within healthy boundaries.

“Especially in the clinical years, it feels like you’re primarily evaluated against your peers,” said one medical student. “It really discourages you from being open or making yourself feel vulnerable, even from expressing that you don’t understand something.”

These circumstances can lead to isolation, and as Poorman explained, doctors can’t give the best care to a patient if they don’t ask questions.

“It’s a shared sense of vulnerability that allows for connections between different people,” said Erica Meninno (M’20), chair of reflection for the School of Medicine’s Learning Societies, which helped organize the event. “And that’s ultimately what we’re all working toward — to feel connected and feel a sense of love and compassion for one another.”

The ‘Perfect’ Physician

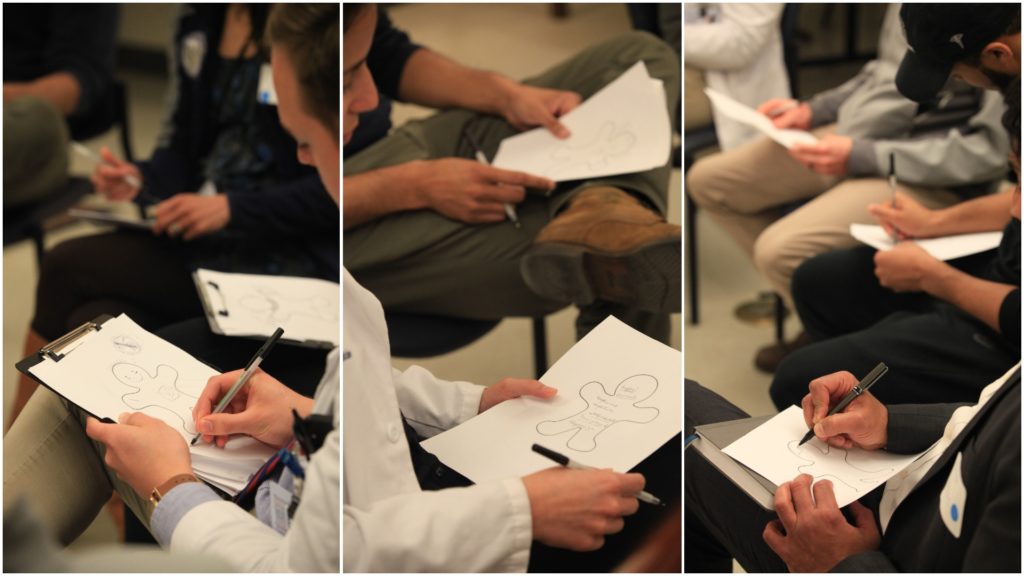

When students in the Gifts of Imperfection discussion group were asked to illustrate their perception of the “perfect” physician, many created what they later admitted were unrealistic representations.

Some of the drawings, which were produced on paper outlined with metaphoric, cookie-cutter gingerbread people, were based on individuals students admired, including mentors. Others illustrated characteristics they simply strived to have.

Playfully explaining his drawing to laughter from those around him, one student gave a caricatured, yet for many medical students in the room, sincere and relatable description of the perfect physician.

“He’s got IV coffee already set-up and hasn’t blinked in 72 hours. He’s laser-focused, only focused on his patients and nothing else, and he does not require any sustenance. He doesn’t stop for anything,” the student explained.

Another student, who started by drawing a smile on her gingerbread physician, explained that, in a way, physicians are always expected to have a smile on their face, notwithstanding whether they truly feel happy in that moment.

She also indicated in her drawing that the perfect physician has a well-rounded lifestyle, often engaging in hiking and other recreational activities. However, she doubted that there might actually be time for leisure if this perfect physician still intended to always have the latest medical knowledge and an impeccable approach to patient care, advocacy and research.

“At different points in your career and your life, there will be different standards you set for yourself,” said Sarah Kureshi, MD, MPH, an assistant professor of family medicine at the School of Medicine who helped lead the discussion.

She used the example of working out twice a day on her college track team, only to realize later as a medical student that the regimen was no longer sustainable with a much more rigorous academic schedule.

“It was hard for me to let go of that,” Kureshi said. “But it goes back to being adaptable and flexible. I feel like that’s one of the best ways to be a good physician and an overall balanced person.”

Seren Snow

GUMC Communications