Nicotine Researcher Honored for Contributions to Study of Addiction

Posted in GUMC Stories

FEBRUARY 28, 2014—A Georgetown University Medical Center researcher who has spent three decades researching nicotine’s effects on the human brain has received a prestigious award honoring his contributions to the field.

FEBRUARY 28, 2014—A Georgetown University Medical Center researcher who has spent three decades researching nicotine’s effects on the human brain has received a prestigious award honoring his contributions to the field.

The Society for Research in Nicotine and Tobacco (SRNT) has announced Kenneth Kellar, PhD, professor of pharmacology at GUMC, as the recipient of the society’s 2015 Langley Award, which honors scientists who have made groundbreaking advances in basic nicotine research in pharmacology, neuroscience or genetics. The award, which is bestowed every three years, will be presented at the SRNT’s annual meeting in Philadelphia Feb. 25-28, 2015.

Kellar says the award is particularly meaningful to him because of its namesake, John Langley, a British pharmacologist whose groundbreaking research in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was the first to describe the function and some of the characteristics of receptors, which, in fact, were nicotinic receptors.

“Langley’s discoveries were made even before neurotransmission was understood; he introduced the concept known as receptive substance, which completely changed our understanding of how drugs act on cells,” Kellar says.

Nicotine and the Brain

Kellar has spent the better part of 30 years studying the effects of nicotine on the brain—and the process by which neurons in the brain communicate through neurotransmission.

Specifically, he and his colleagues have looked at the various subtypes of nicotinic receptors, seeking to understand how they differ depending on their location in the brain, their pharmacology and their regulation.

“To beat the tobacco addiction, you must understand what is happening with these receptors, or else you are just shooting in the dark,” Kellar says.

Research from Kellar’s lab and many others have demonstrated two important features that make nicotinic receptors distinct: they are upregulated, meaning there is an increase in cellular response, and they are rapidly desensitized by nicotine. When people smoke tobacco, they do so to satisfy these nicotinic receptors, Kellar says.

Therefore, the ideal drug to combat addiction would mimic the desensitization caused by nicotine without causing the upregulation in the receptors. The importance of upregulation to the addictive process is a contribution that came out of Kellar’s lab.

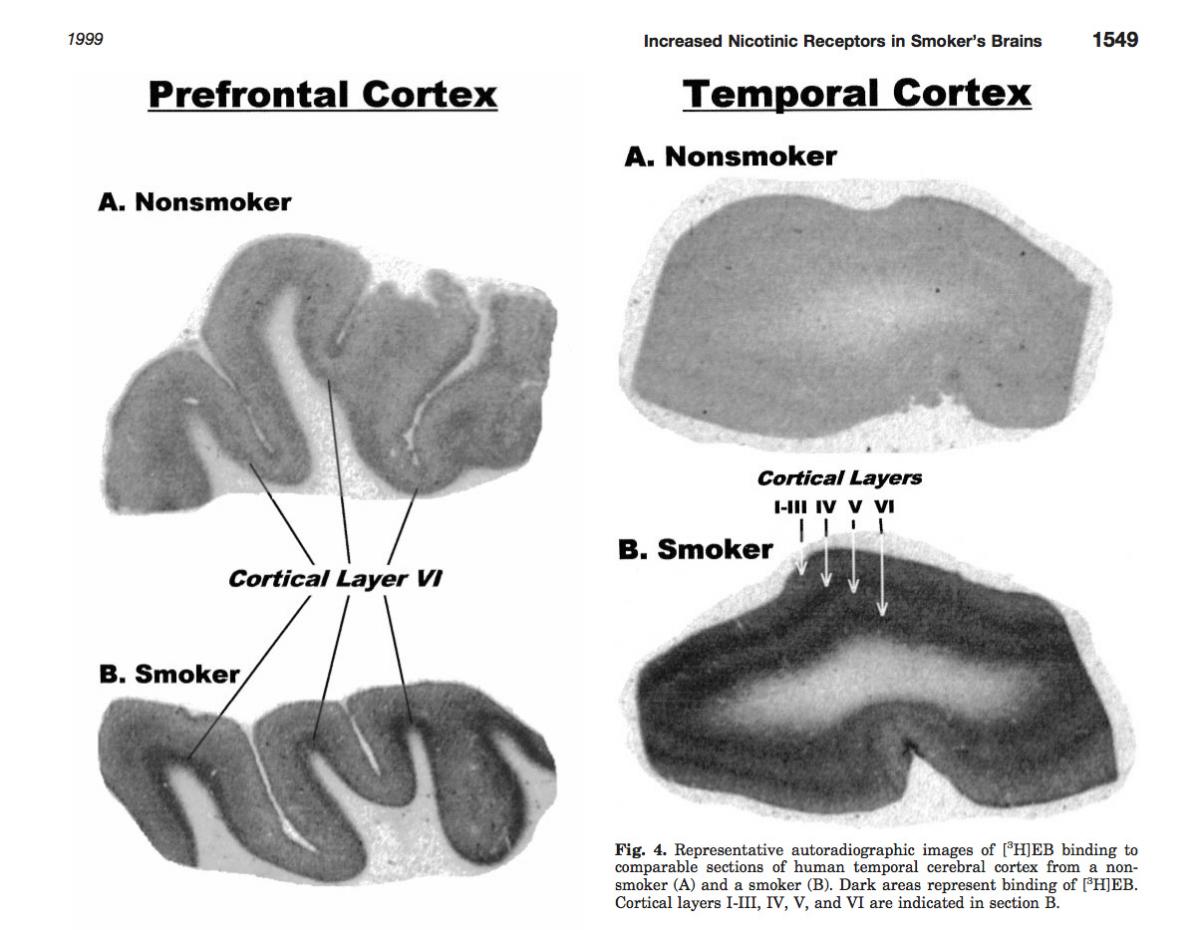

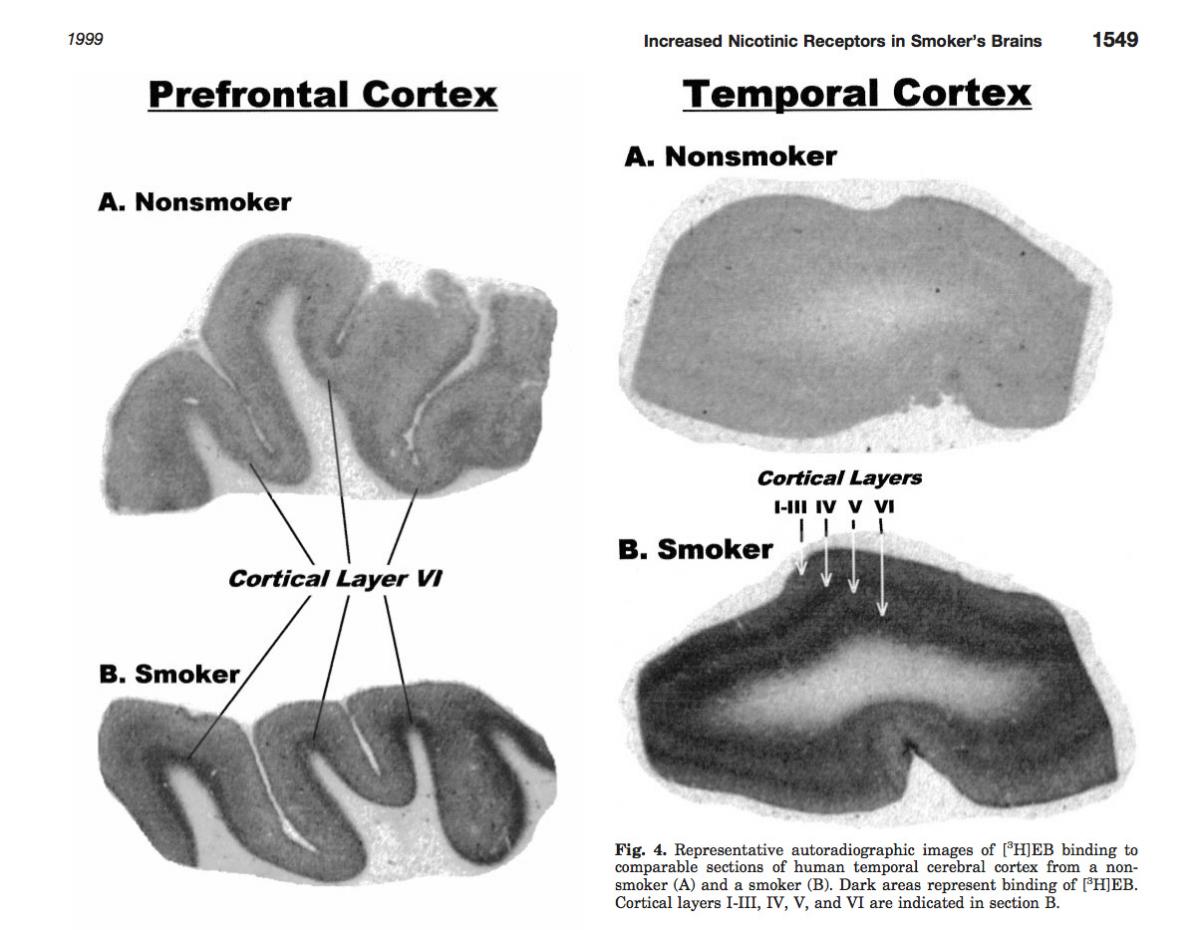

After discovering that nicotine caused upregulation of nicotinic receptors in rats, Kellar and his research colleagues later published the first images of these receptors in the brain of a human smoker in the Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. These images helped shape the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s 1996 ruling that reclassified nicotine as a drug, according to Jack Henningfield, PhD, professor of behavioral biology at The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, who played an intrumental role in sharing Kellar’s images with regulators.

After discovering that nicotine caused upregulation of nicotinic receptors in rats, Kellar and his research colleagues later published the first images of these receptors in the brain of a human smoker in the Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. These images helped shape the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s 1996 ruling that reclassified nicotine as a drug, according to Jack Henningfield, PhD, professor of behavioral biology at The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, who played an intrumental role in sharing Kellar’s images with regulators.

“Dr. Keller’s work helped the FDA to understand that nicotine as powerful and potent brain acting drug when the tobacco industry was arguing that nicotine did not produce substantial pharmacological effects,” says Henningfield. “It is hard to overstate the importance of his work.”

SRNT leadership praised Kellar’s work as having shifted researchers’ understanding of nicotine addicition.

“The Langley Award recognizes scientists that have made groundbreaking advances in basic nicotine research. The work of Dr. Kenneth Kellar exceeds this definition,” says SRNT President Thomas Gould, PhD. “His studies … led to a fundamental paradigm shift in understanding the biological effects of nicotine and in the development of treatments of nicotine addiction. The field could not be where it is at today without this fundamental finding.”

Rethinking Harms of Nicotine

Kellar uses the word “cure” in the context of nicotine addiction—a term not often embraced by the scientific community. He has hopes of one day being able to cure the addiction by finding a drug that will desensitize nicotinic receptors without upregulating them—thereby beating both conditions that allowed the addiction to take hold in the first place.

Furthermore, he is quick to emphasize that nicotine is “just a drug” and in small doses is not particularly harmful on its own. The harm comes from cigarettes, with the accompanying carbon monoxide and all the other toxic components of burning tobacco.

In fact, the research of Kellar and his colleagues indicates that nicotine might even be helpful in some conditions, including some cognitive disorders.

In a study published in the journal Neurology in 2012, Kellar and his colleagues from GUMC, Duke University Medical Center and the University of Vermont determined that in a population of elderly non-smokers, nicotine patches used over six months were safe and might be useful to improve some of the deficits seen in mild cognitive impairment, which is often a precursor of Alzheimer’s disease.

“There is a lot of history in this field and many very good scientists doing important work in the study of nicotine, including many graduate students and post-doctoral fellows who I have worked with here at Georgetown. This award is very meaningful to all of us,” Kellar says.

By Lauren Wolkoff

GUMC Communications