Literature and Medicine Encourages Empathy in Medical Students

Posted in GUMC Stories | Tagged literature and medicine track, School of Medicine

(May 10, 2019) — Daniel Marchalik, MD, assistant professor of urology at Georgetown University School of Medicine and medical director of physician well-being at MedStar Health, has always been interested in the relationship between literature and medicine.

Marchalik earned his undergraduate degree in English Language and Literature from Rutgers University, which led him to create a literature and medicine elective during his time as a medical student at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School.

The literature and medicine elective took hold at Rutgers, becoming a formal elective program for medical students. Soon after starting his residency in urology at Georgetown, Marchalik felt the pull toward literature once again.

“When I arrived at Georgetown, I really missed literature and decided to put together an elective pilot,” he said. “It was so well received by the medical students that it grew into a formal track at the school.” The Literature and Medicine Track at Georgetown University School of Medicine debuted in 2013.

Exploring Medicine Through a Different Lens

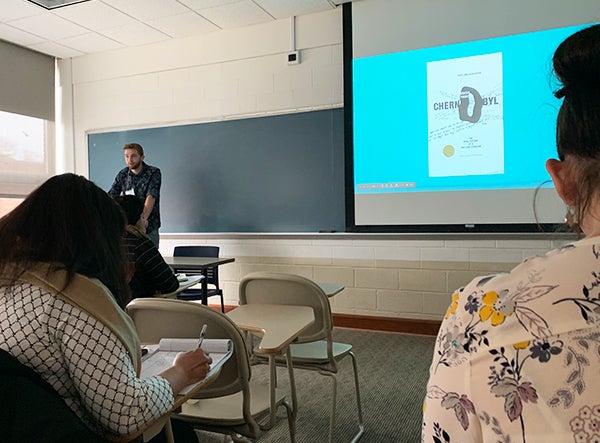

Students in the Literature and Medicine track engage in “the intersection of literature, narrative studies, medical narratives and medicine,” and are required to read eight fiction books per year. They also attend a monthly discussion in a “book club” format.

In their third and fourth years, students attend a monthly hourlong meeting dedicated to the exploration of narratives within medicine and complete a scholarly capstone project.

The capstone projects often take a life of their own, with students presenting at international conferences, having work published in journals or creating programs at the School of Medicine, such as the Obituary Writing Program, started by Bethany Kette (M’20).

Kette wanted to better understand the lives of the people who donated their bodies to medical education and worked with Marchalik and Washington Post reporter Emily Langer to create the writing program, which is now part of the Anatomical Donor Program.

The Literature and Medicine Track also hosts trips to museums in Washington, D.C., such as the National Gallery of Art and the National Museum of African American History and Culture to add further context to topics they’re discussing in the books. It has brought several authors and speakers to campus to discuss their work or a relevant topic.

“I wanted to branch outside of medicine and have a more holistic approach to round out the clinical knowledge I would be getting in the classroom,” said Victor Wang (NHS’15, M’19), author of an article in the Georgetown Medicine Magazine on mental illness and literature.

“We talk about issues related to immigration, race, gender, sexuality, etc.,” Wang added. “It rounds out my ability to understand myself in the context of society, but also to understand my patients in the context of their own story, what they bring to the hospital.”

Increased Empathy Toward Patients

Empathy and understanding is a frequent discussion topic among students in the track. For example, Johan Clarke (M’19) focused his capstone presentation on the theory of “abject horror,” which he credits to helping him reflect on how he views patients.

“I was interested in abject horror in medicine, and how we’re fascinated with the body going wrong and how that can objectify patients,” he said. “It helped me think about moments in my career where I have done that and how it’s affected my relationship with the patient and the patient’s relationship to themselves and their body.”

Clarke presented his work at the Pacific Ancient and Modern Language Association (PAMLA) Annual Conference in 2018 and the American Comparative Literature Association (ACLA) Annual Meeting in 2019.

“The most important lessons I’ve learned from the track are empathy and awareness,” said Clarke.

“We read several books where it was hard to empathize with the narrator and we had to discuss why it was difficult,” he added. “I think that’s going to help me when I’m having a rough day or working with a rough patient. I’ll be able to sit down and think about how my identity is clashing with their identity.”

Claire McDaniel (C’14, MBA’19, M’19), author of eight articles in the BMJ on literature and medicine, echoed Clarke in saying that learning how to listen to other people’s stories was the most important skill she learned after four years in the track.

“It helped me stay empathetic after long hours or stressful classes. It made me think beyond the hospital, which will make for more well-rounded and compassionate physicians,” she said.

For Wang, the track has helped him adopt a new lens when working with patients. “This track teaches you how to see outside of yourself and your own limitations. There’s this understanding that there are boundless walks of life and you can learn from any individual patient.”

Improving Medical Student Well-Being

In his research, Marchalik has found that reading for pleasure prevents burnout, something students on the literature and medicine track can confirm.

“We’ve done a couple of studies on burnout in urology residents in the United States and Europe, and have found that reading for pleasure is one of the few activities that’s really protective against burnout,” he said.

“It has been very grounding,” said Wang. “Sometimes you feel like you’re wading through all these different waters and obstacles in medical school and at the hospital. Being able to take yourself out of that, for even an hour, helps you recharge and look at things from a different perspective.”

For McDaniel, reading is cathartic, and discussing the books with her peers has helped her stay grounded during the highs and lows of medical school.

“It’s a pleasant thing to do in your free time and provides a contrast to the work itself,” she said. “Doing this cathartic thing and getting together to talk about it with like-minded people has really helped to keep us from burning out.”

Giuliana Cortese

GUMC Communications