Helping Transform Afghanistan

Posted in GUMC Stories

A trip to the United States and Georgetown University wouldn’t be complete for Afghan President Hamid Karzai without acknowledging Phyllis Magrab, PhD, director of the Georgetown University Center for Child and Human Development.

A trip to the United States and Georgetown University wouldn’t be complete for Afghan President Hamid Karzai without acknowledging Phyllis Magrab, PhD, director of the Georgetown University Center for Child and Human Development.

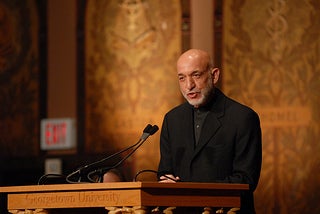

Shortly after Karzai left the White House for his meeting with President Obama on January 11, he addressed an audience on the Hilltop about his country’s changing relationship with the United States.

At the end of the hour-long event, Karzai, Magrab, and Georgetown University President John J. DeGioia, PhD, shared a brief conversation in which Karzai told them that he now believes something he never would have said two years ago. “He told me ‘My country will make it,’” Magrab says. “He basically implied that Afghanistan will survive and find a way to advance while folding in all members of its society, including the Taliban.”

The link tying Karzai, DeGioia and Magrab together is their desire to improve the lives of women and children in Afghanistan. In January 2002, Karzai, then Afghan Interim Authority Chairman, and President George W. Bush announced in a joint statement, following a White House meeting, that they would launch a joint U.S.-Afghan Women’s Council to “promote public-private partnerships and mobilize resources to ensure women can gain the skills and education deprived them under years of Taliban misrule.” The bi-national Council was, shortly thereafter, officially established as a presidential initiative in the U.S. State Department.

In late 2006, Laura Bush announced a new partnership between the Council and Georgetown University to help empower Afghan women through educational opportunities, skills training, improved political and legal participation, and access to medical care. In 2008, DeGioia, who serves as one of the two U.S. chairs of the council, asked Magrab to run the Council as its vice chair.

In late 2006, Laura Bush announced a new partnership between the Council and Georgetown University to help empower Afghan women through educational opportunities, skills training, improved political and legal participation, and access to medical care. In 2008, DeGioia, who serves as one of the two U.S. chairs of the council, asked Magrab to run the Council as its vice chair.

“At the time I knew nothing about the Council, but I am very devoted to womens’ and childrens’ issues…so, ergo, I said yes,” Magrab remembers. She then was able to convince the State Department to “detail” someone to work out of her university office as the Council’s Executive Director, a post now held by Lauren Lovelace.

Magrab is well known for her ability to secure and then administer large federal grants through her lifelong work in changing systems of care for children and youth with developmental disabilities and other special health care needs. She is also a consultant to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and holds a UNESCO chair. But the Council required a different skill set.

“Our job is not just to keep the Council glued together, but to broker projects that are suggested to us. We need to make sure they are sound, that they can be funded, and that they will be well received,” she says. The 60 programs organized to date are focused on literacy, self-sufficiency, business education, health care, and leadership. They include such diverse projects as Magrab’s mobile literacy project, where mobile phone technology is used to promote basic literacy among Afghan women through text messaging and classroom sessions; a project from womens’ accessories designer Kate Spade to train and employ Afghan women artisans; and production of the Afghan Family Health Book, a “talking book” which teaches basic health, hygiene, and disease prevention, distributed to hospitals, clinics and women’s centers throughout Afghanistan.

Despite the challenges and roadblocks of working with a country in conflict — “trade agreements, export issues, security issues” — Magrab can see a transformation underway in Afghanistan. Karzai spoke to such progress in his Georgetown address, saying that in 2001, only a few thousand children were going to school, none of them were girls. Now there are 8 million school students and 45 percent are girls, he said.

Karzai added that, within the last three years, the schools are safe and secure for these girls. And to further their education, Afghanistan now has 30 public and private universities, he said.

Karzai added that 70 of the 240 members of the Afghan parliament are women. Women are returning to the work place, girls are returning to school, universities are coming back, as is communication due to a burgeoning supply of mobile phones and computers, he said.

Magrab sees no end to the progress that the Council can make in a post-conflict Afghanistan. She borrows the words from one Council member who described an ever-expanding road to success: “Initially, it felt like digging at a mountain with a spoon; then the spoon became a shovel, and the shovel became a bulldozer.”

By Renee Twombly, GUMC Communications