Harold P. Freeman, Champion of the Underserved, Receives Top Honors at 10th Annual Convocation

Posted in GUMC Stories | Tagged university awards

November 21, 2017 — With a grand processional entrance by Georgetown University Medical Center faculty in full, colorful regalia, the GUMC Fall Convocation began its 10th annual awards ceremony in front of a packed house in the Research Building auditorium on November 16.

As in years past, the highlight of Convocation was the bestowing of the Cura Personalis Award that recognizes a health professional who has made outstanding contributions to human health guided by compassion and service, and the recipient’s keynote address. This year’s recipient was Harold P. Freeman, MD, a champion of the poor and underserved.

As reflected in the award recipient, the theme for both the awards ceremony and the colloquium held earlier in the day was health disparities, an affirmed priority area for GUMC.

Groundbreaking efforts

“Dr. Freeman has devoted his life to advancing health and eliminating health disparities in vulnerable and underserved communities across our country,” said Edward B. Healton, MD, MPH, executive vice president for health sciences at GUMC and executive dean of School of Medicine.

“I have admired his work over the entire span of his long career, and so it is a very special pleasure for me to stand with Dr. Freeman on this podium today,” he added.

Freeman’s most important work has included groundbreaking efforts in reducing health inequities, including the development and implementation of the concept known as patient navigation.

Inspiring ancestors

During his keynote address, Freeman, a surgical oncologist who spent his professional career focused on the underserved in Harlem, reflected on his ancestors, enslaved since before the signing of the Declaration of Independence, he said.

His ancestors eventually “bought” their freedom.

“If my ancestors could do that, I was challenged to do as much as I could and more if I could.”

Freeman stayed in Washington to attend medical school at Howard University. He began his career at Harlem Hospital where he witnessed health disparities and injustice towards his poor and black cancer patients in the breast clinic that he ran.

‘This changed my life …’

“Many of those women were coming in too late,” Freeman explained. “They were all poor. They were all black. Some of the women had visible masses. You don’t have to touch it – it’s there. Some of the masses were bleeding when I first saw them. This changed my life. … I had to do something more. I could not accept that people were coming in this late and dying.”

After talking to the women, he learned that for many, this had not been their first visit to a doctor. Many had been to the emergency room and turned away because a breast mass didn’t represent an emergency and they didn’t have insurance. But Freeman recalled the women explaining they had other concerns, like food, housing and crime in the streets.

Freeman said he knew he had to do more. “It didn’t make moral sense to me,” he said.

Opened Free Clinics

As director of surgery at Harlem Hospital, he opened a free Saturday screening clinic at Harlem Hospital in 1979, and he founded the Breast Examination Center of Harlem, a program that continues today at Memorial Sloan Kettering to provide free breast cancer screenings.

“I solved the challenge of screening people but that wasn’t enough, because some of the women are lost after a finding [on their mammogram],” he said. “And so I knew I had not really solved the problem.”

Freeman became president of the American Cancer Society in 1988. Believing that poverty more than race played a role in the outcomes of his cancer patients, Freeman launched a listening tour across the country to learn about the challenges faced by poor people with cancer, whether in California, New Jersey, or Texas.

He heard the same message repeatedly from poor people of all races. “They said ‘We meet barriers when we attempt to get into, and through, this very, very complex health care system,’ ” Freeman recalled. “I thought, if people meet barriers, maybe we can navigate them.”

And with that, Freeman’s most innovative idea had taken root.

The Birth of Patient Navigation

Freeman created and implemented the concept of “patient navigation” in 1999. It is intended to match a trained individual with a cancer patient to guide the individual through the complexities of the health care system – from screening to diagnosis and through the completion of treatment.

Freeman first added navigation to the free screening clinic in Harlem, and it was a stunning success. He and his colleagues published data in 1995 describing its impact on a patient’s outcome.

“We had changed the five-year survival from 39 percent, before screening and intervention, to 70 percent,” Freeman told the audience, which erupted in applause.

The data were presented to Congress, and in 2005, George W. Bush signed the National Patient Navigation Act.

Navigation Institute

Freeman went on to found the Harold P. Freeman Navigation Institute, a program that provides navigator training. His approached has been embraced by organizations around the country including the Capital Breast Cancer Program, a Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center program in southeast Washington.

Freeman also was founding director of the National Cancer Institute’s Center to Reduce Health Disparities. He is a member of the National Academy of Medicine and has received a Lasker Award for public service — one of the numerous accolades Freeman has garnered in his lifetime.

Unwavering Dedication

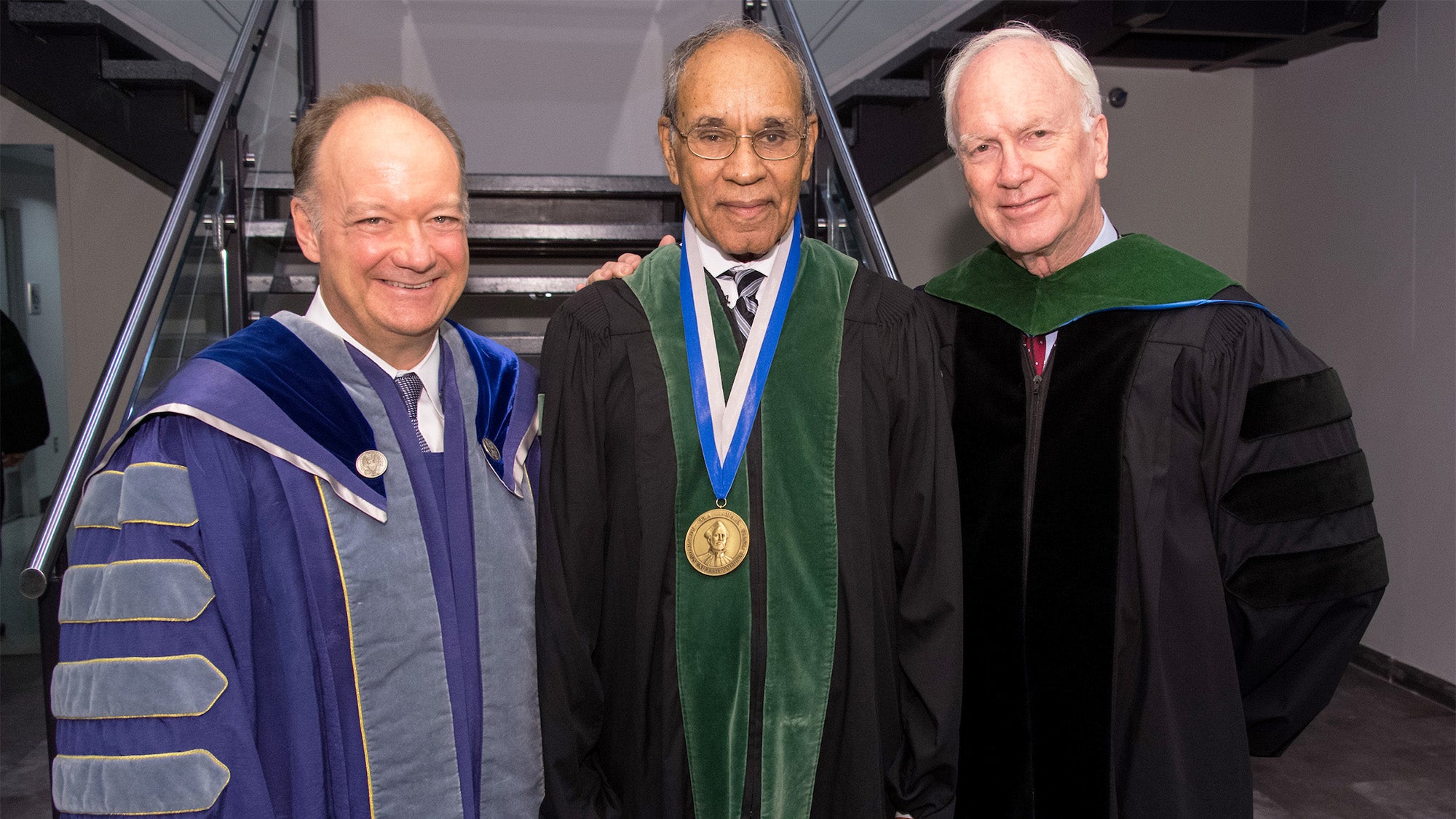

At the conclusion of his address, Georgetown University President John J. DeGioia read the citation for the Cura Personalis Award.

“Georgetown University Medical Center celebrates the accomplishments of an individual who has worked tirelessly to reduce health disparities by developing programs to eliminate barriers that often prevent patients from accessing critical screening and treatment services.

“For his unwavering dedication to the underserved, for his achievements as an innovator, and for his service to national organizations through which he worked to address health disparities, Georgetown University Medical Center presents Harold P. Freeman MD, with its highest honor, the Cura Personalis Award.”

Karen Teber

GUMC Communications