For Harley, Patient Care is ‘the Best Part of the Job’

Posted in GUMC Stories | Tagged diversity, faculty profile, medical education, School of Medicine

(February 26, 2022) — When asked about the best part of his job, Earl H. Harley, Jr., MD, FACS, FAAP, answered quickly, pulling colorful drawings and cards off his bulletin board and out of a desk drawer.

“The best part of my job is the patients,” said Harley, professor of otolaryngology and pediatrics at Georgetown University School of Medicine and chief of pediatric otolaryngology at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital. “You see them growing up, and it’s just the best part of the job.”

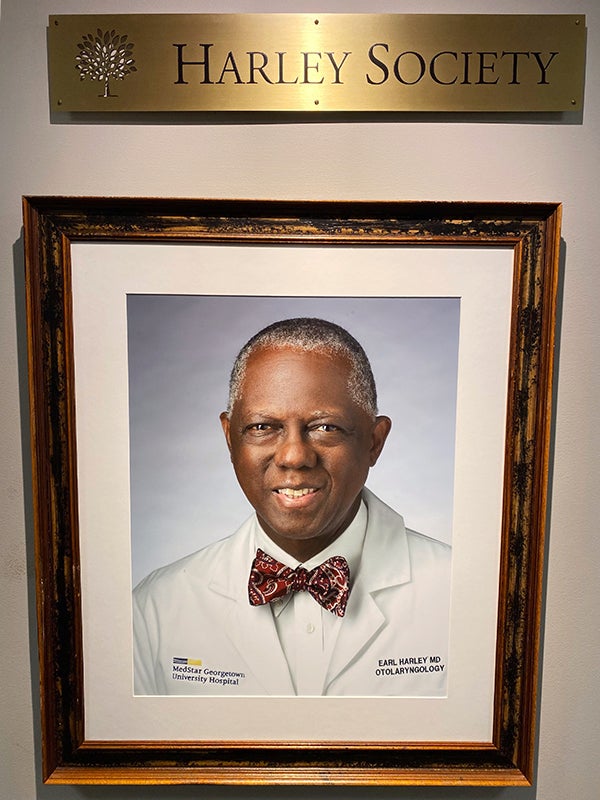

The drawings and cards from his patients that he’s collected over the years are just one measure of Harley’s impact as a professor, researcher and clinician. In recognition of his distinguished career, a learning society was named in Harley’s honor, the first named for an African American at the School of Medicine.

“That was an honor, that was a surprise,” he said. “And I’m still honored and humbled by it.”

Educated by HBCUs

Born in Jacksonville, Florida, Harley was raised in Detroit. When he told his father, a pastor, that he was interested in a career in engineering, he was encouraged to consider becoming a pharmacist. Reviewing a book from the Department of Education, Harley read that he could become a pharmacist after five years of school or he could earn his medical degree in six years.

“If I spend one more year, I can be a medical doctor — that was my thought process as a high school student,” he said. “That was what got me here, was my father throwing out the possibility of the health care field, that it was a good field for me.”

After his family was relocated to Delaware for his father’s church, Harley chose to earn his undergraduate degree in chemistry at Delaware State University. “They had two four-year universities in Delaware, one Black and one white,” he said. “Delaware State was the Black school.”

“It was an interesting experience,” Harley added. “Delaware was still very segregated at the time. Coming from Michigan, I had never experienced anything like that.”

From Delaware State, Harley went to Howard University College of Medicine, where his professors were actively engaged in the civil rights movement in addition to their academic careers, including William Montague Cobb, MD, PhD, a physician and noted anthropologist who was the first African American to earn a PhD in the subject. “They weren’t just medical doctors, they were civic leaders,” he said. “These people who grew up in segregation were really involved in civil rights at the time.”

Pursuing Pediatric ENT

Harley earned his medical degree in 1971, then began his career in the U.S. Navy, completing an internship at National Naval Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland (now Walter Reed National Military Medical Center), then a residency in pediatrics at San Diego Naval Regional Medical Center. After serving at the Naval Medical Clinics in Okinawa, Japan, and Indian Head, Maryland, he trained and served as a Navy flight surgeon.

In 1980, Harley began to train in otolaryngology residency at Oakland Naval Hospital in California. He later served as chief of otolaryngology at Long Beach Naval Hospital and returned to San Diego as an attending otolaryngologist before starting his training as a pediatric otolaryngologist.

“Pediatric ENT is a young specialty,” Harley said. “It’s only about 45 years old today. When I trained as a pediatrics ENT fellow, I was in the third class of fellows at the Children’s Hospital National Medical Center here in Washington, D.C., and this was one of the few fellowships in the country.”

After completing two pediatric ENT fellowships in Washington, D.C., and Boston, Harley again returned to San Diego as the first pediatric otolaryngologist in the U.S. Navy and vice chair of the department. “If you look at San Diego, it’s a huge military town,” he said. “There was obviously a need, so I went there and started a program in the Navy.”

‘I’m Glad I Did Not Become an Engineer’

Retiring as a Navy captain in 1993, Harley joined the faculty at the School of Medicine as assistant professor of otolaryngology and pediatrics and an attending pediatric otolaryngologist at Georgetown University Hospital.

When it comes to patient care, most of Harley’s work involves improving quality of life. “They usually don’t have devastating diseases, but they have these things that might be impacting school performance, because they’re not able to sleep well because of their tonsils,” he said. “You can make a relatively simple intervention that makes a tremendous difference in the lives of children.”

One of those patients later became a student of his. Bria Johnson (M’22) first met Harley as a 5-year-old suffering from chronic ear infections. “He is an exceptionally talented, compassionate pediatric otolaryngologist,” she said. “He has a love for children and for healing beyond words.”

In addition to his patients, Harley has made a difference in many lives through his work as a professor. “He has mentored countless students, residents and many of us as faculty, as well as our GEMS program for over two decades,” said Stephen Ray Mitchell, MD, MBA, dean emeritus of the School of Medicine.

When Johnson started at Georgetown as a medical student, Harley became her mentor. “As a minority student, it proved to be even more comforting to have a mentor who looked like me,” she said. “He never failed to answer my questions, organize quick meetings and provide guidance as I navigated through medical school.”

As the namesake for one of the learning societies, Harley leads the incoming medical students as they recite the Hippocratic Oath for the first time at the White Coat Ceremony. “It’s meaningful to go through it, because at the end, each time I’ve given it, I end the oath by stating to the students, ‘Welcome to the house of medicine,’” he said. “It’s welcoming a whole new generation of doctors.”

“I’m glad I did not become an engineer, because I wouldn’t have had the rewarding career that I have, dealing with the patients and medical students and otolaryngology residents.”

Kat Zambon

GUMC Communications