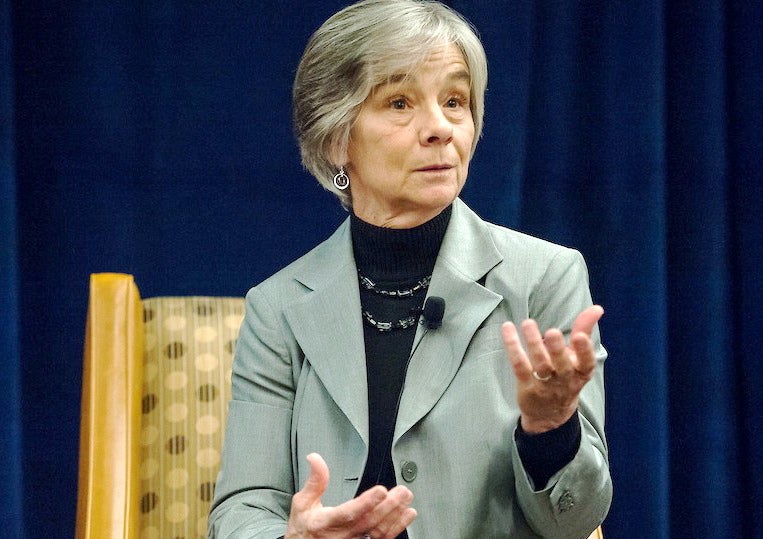

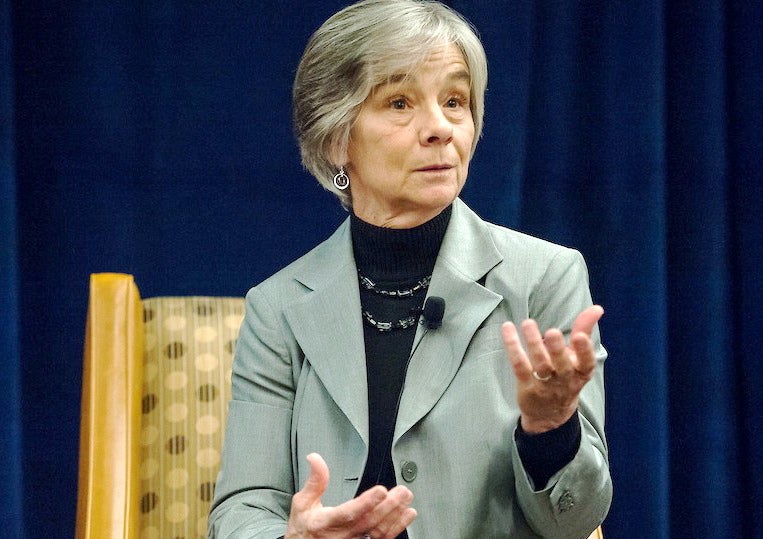

Darlene Howard: Study of the Aging Brain a Career-Long Fascination

Posted in GUMC Stories

Darlene Howard, PhD, Georgetown University’s Davis Family Distinguished Professor, was in her 20s when she began studying how a normal, healthy mind and brain age. The newly minted psychology professor was inspired partly by the notion that the first step in learning how to fix something broken is the knowledge of how it is supposed to work.

Darlene Howard, PhD, Georgetown University’s Davis Family Distinguished Professor, was in her 20s when she began studying how a normal, healthy mind and brain age. The newly minted psychology professor was inspired partly by the notion that the first step in learning how to fix something broken is the knowledge of how it is supposed to work.

Today, nearly 40 years later, she is an expert on which cognitive and neural systems decline and which are spared during aging.

The irony that she now is a demographic of her own research is not lost on Howard, nor is the evidence that the brain is malleable and can reorganize and redirect itself.

“The older brain often just does tasks differently. It uses both sides of the brain, is more bi-lateral and more prefrontal. This looks like it might be good: adaption could be based on experience,” she says. “The brain adapts to its own aging.”

The Center for Brain Plasticity and Recovery

Scientists refer to the brain’s ability to adapt as “plasticity,” which is abundant in younger brains and enables children to learn quickly. Many researchers, including Howard, believe harnessing this youthful ability could lead to therapies for brain diseases and disorders.

Howard is a member of the newly formed Center for Brain Plasticity and Recovery, a Georgetown University/MedStar National Rehabilitation Network collaboration that focuses on the study of biological processes underlying the brain’s ability to learn, develop and recover from injury.

Researchers at the Center aim to find ways to restore cognitive, sensory, and motor function caused by neurological damage and disease such as traumatic brain injury and dementia. The focus initially will be on stroke recovery.

The timing for this research is impeccable. The nation’s estimated 70 million baby boomers are aging in unprecedented numbers, the economic repercussions of which are sure to be dramatic in an uncertain and stressed economy. With aging comes devastating diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s — the need to address these health issues and to promote successful aging has never been as urgent.

A psychologist and project director of the Cognitive Aging Laboratory at Georgetown, Howard has spent decades investigating which cognitive functions (remembering your anniversary) and which neural systems (neurons and other architectural components that make up the gray, sponge-like brain) decline and which are spared in the natural course of aging.

Her work has been funded continuously since 1978 by the National Institute on Aging, a tribute to her widely admired expertise and outstanding productivity in research endeavors.

Howard is kinetic, warm and plainspoken when asked about the deepest mysteries of the brain. She defines the oft debated philosophical issue of the mind versus brain succinctly: “The brain is three pounds of biological tissue between the ears that enables the mind,” she says, and smiles.

A Rare Glimpse into Scientific Inquiry

The starting and sustaining mystery of her life’s work, Howard says, can be summarized in the question “How is it that we know things that we didn’t try to learn and don’t know we learned?”

Questions she uses to illustrate her research offer a rare glimpse into how simple ideas can launch scientific experiments, lead to ground-breaking research, which may eventually translate into treatments for people suffering from illness.

For example, Howard asks, when you turn on a light switch without thinking, how do you know where it’s located? What lets you know how to get hot water instead of cold when you turn on the faucet? How do you know just the number of steps to go down in a familiar staircase, even though you’ve never counted them?

The answers to these questions form an increasingly important field within psychology, the study of implicit learning. “It is much more important for adapting to new places and people than more conscious forms of learning,” she says. “But because implicit learning is outside of awareness, people typically don’t realize how important it is.”

Known variously as “thinking without thinking,” “learning by osmosis” and the “adaptive unconscious,” the inquiry into such learning has the potential to revolutionize how we understand our experiences and to optimize approaches to learning new information.

“The kind of learning we are studying is the kind that happens when people are just going about their daily business, when they are focused on living, not on memorizing or learning,” Howard explains.

“It is involved in learning new motor skills such as bike riding, learning new languages, picking up new cognitive skills such as chess playing and in developing intuitions about how other people will act.”

Howard’s body of work dovetails with that of the new Center for Brain Plasticity and Recovery, where multi-disciplinary research teams work to gauge the plasticity of brains to understand if and how they regain function.

Howard’s Cognitive Aging Lab uses behavioral and neuroimaging techniques such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), sophisticated techniques that have galvanized neurological research, Howard says. Before these inventions, scientists could only study the brain after people died; now they can see the living brain as it goes about its daily business.

Howard’s lab, in collaboration with researchers at The Catholic University of America, focuses on implicit learning that occurs without intent or awareness, on why some forms of learning and memory decline while other kinds do not, on whether these differences are related to changes in the brain and on how learning and memory can be maximized at all ages.

Members of the lab research the relationship between different forms of implicit learning and genotype, environmental factors (such as stress and time of day), individual differences (such as reading ability, lifestyle and amount of exercise) and time spent outdoors in natural environments.

“What’s really neat, and has only become clear in the last 10 or so years, is the aging brain compensates: older brains do tasks differently than younger brains,” rather than ceasing to do the tasks, Howard says.

By Victoria Churchville, GUMC Advancement