Georgetown Global Health Experts Apply Past Lessons to COVID-19

Posted in GUMC Stories | Tagged 2019 Novel Coronavirus, Center for Global Health Practice and Impact, Center for Global Health Science and Security, COVID-19, Ebola, global health, HIV, School of Medicine

(April 21, 2020) — As COVID-19 cases continue to spread around the globe, there is still much to be understood: how long drastic “social distancing” measures will be necessary, whether there will be a resurgence months from now, and to what extent viral mutations might impact clinical outcomes, among many other critical questions.

As the public looks to experts for answers in the face of the unknown, those same experts look to the past.

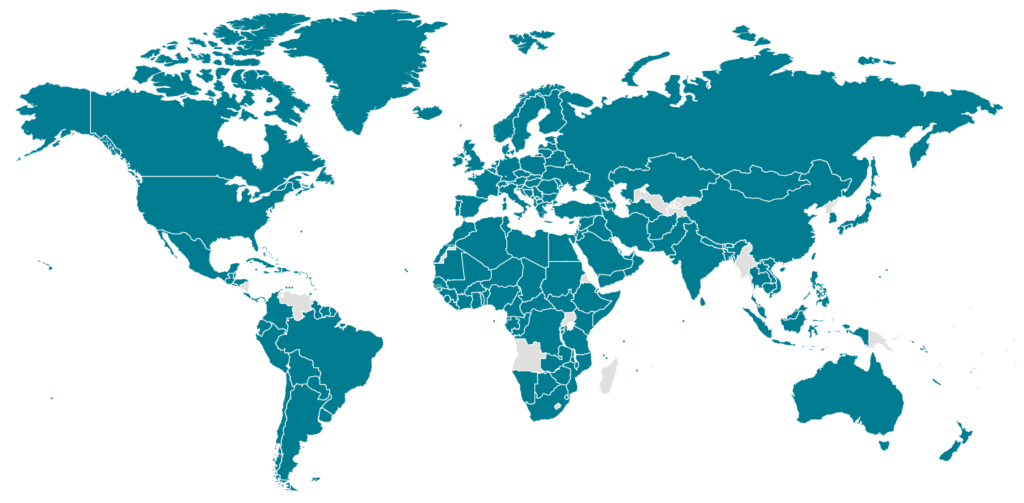

While acknowledging that much of the novel coronavirus pandemic is unprecedented, particularly in terms of its geographic reach and infection rate, Georgetown researchers point to some universal lessons from previous outbreaks.

For example, the 2014-2015 Ebola epidemic in West Africa offers valuable information about what works and what does not work in terms of a coordinated and effective public health response.

“The countries that succeeded in keeping Ebola at bay, such as Mali, Senegal and Ivory Coast, did so because they responded by using the health infrastructure that was already there, and by using the community health care workers to help monitor, report and be able to respond immediately,” said Mark Dybul, MD (C’85, M’92, H’08), co-director of Georgetown’s Center for Global Health Practice and Impact (CGHPI) and professor at the School of Medicine.

Dybul, who previously served as executive director of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria and as U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator in charge of implementing the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), said African countries currently have systems in place from their Ebola response efforts that, when deployed properly, can prove helpful for minimizing the spread of COVID-19.

“If you came across the border from Guinea to Mali, for example, they knew exactly where you were and if you had a fever. If you got an infection they could identify and trace where you had been,” he added.

Primed Populations

Countries with experience containing outbreaks are also better equipped from a public education standpoint, according to Rebecca Katz, PhD, MPH, a professor of microbiology and immunology who directs Georgetown’s Center for Global Health Science and Security (CGHSS).

Having spent her career studying pandemics and public health preparedness, Katz and her team have worked extensively to help governments shore up public health infrastructure and build capacity to deal with major disease outbreaks.

“I think that for countries that have had a lot of experience with outbreaks, it is easier for them to act quickly and for their populations to immediately follow the guidance that is issued,” Katz said. “We are seeing this in Southeast Asian countries that had experiences with SARS, MERS or influenza. These countries have gone through it, and they were ready and more prepared this time around.”

Ready to Spring into Action

Similarly, having mechanisms in place that enable quick coordination among relevant public health authorities, both horizontally across different parts of the health system, as well as vertically from the national down to the local levels, is key.

Countries that have dealt successfully with epidemics understand what it takes to have the personnel and resources lined up to aggressively manage critical variables early on, which saves valuable time in responding.

Claire Standley, PhD, MSc, assistant research professor within CGHSS, served as the technical lead on a project involving post-Ebola outbreak recovery and rebuilding efforts in the West African nation of Guinea.

“This particular pandemic has biological characteristics that make it more challenging, including primary transmission through respiratory droplets and asymptomatic transmission, that were not an issue with Ebola,” Standley said.

“Yet if you are already set up to immediately hospitalize or isolate people who are sick, and to conduct extensive contact tracing and diagnostics, you have a much better chance of getting a handle on transmission before it gets out of control. So this virus may be harder, but it doesn’t mean that those tools go away — they are still useful,” she added.

Strengthening Local Capacity

These experts agree that building local capacity and investing in community-driven solutions are necessary measures to ensure the world is better prepared for the outbreak.

“With a pandemic, it’s happening everywhere at once to varying degrees. So instead of a localized outbreak where the world parachutes in, nobody is parachuting anywhere right now,” Katz said. “So maybe that’s not ever the right model. Instead, maybe this is an opportunity to really think about how to strengthen capacity in every corner of the world.

Charles Holmes, MD, professor of medicine at the School of Medicine, echoed that COVID-19 has underscored the need to strengthen local capacity.

“The novel coronavirus pandemic has raised the stakes for all of us, and has made the local capacity to deliver health care all the more critical,” Holmes wrote in a recent article in Think Global Health.

Drawing on his experience as chief executive officer of a large Zambian nongovernmental organization working primarily on HIV and tuberculosis, Holmes stressed that this pandemic necessitates an all-hands-on-deck approach, including governments and civil society organizations at the international and global levels.

“Local organizations are particularly well-positioned to leverage their permanent presence [in countries],” he wrote.

Dybul and colleagues at CGHPI are currently working in a handful of countries, including Kenya, Malawi, and Eswatini, to tap into and support local communities of practice around public health issues, namely HIV, in order to link local health service delivery with national policymaking.

Long before the novel coronavirus was on everyone’s lips, they were convinced that leveraging the connections and innovation at the local level holds the key to some of the world’s most vexing public health challenges.

“There is no problem a community cannot solve for itself from a health care delivery perspective,” Dybul said.

Asking Hard Questions

Still, the lessons of the past can only take us so far — at least for now. Experts are mindful that the current pandemic is unparalleled in modern history, making it difficult to draw comparisons.

“For most people alive today, this is a very unique situation and the first true global deadly pandemic that we have ever seen. Recent epidemics never got to this level, in that they never spread from one part of the world to the rest of the world,” Dybul said.

Yet perhaps because of the magnitude of the disruption people are experiencing, now is the exact right moment to be asking hard questions about how prepared we actually are to contend with a pandemic, and to work toward sustainable, country-led solutions.

“This experience should make clear to everyone that our health depends on the world’s health. Our interest in the health of the world is more than humanitarian — we are dependent on one another,” Dybul said. “That connectivity is not frightening. It is inspiring.”

Georgetown is well-positioned to lead in asking — and responding to — the hard questions, according to Katz.

“Georgetown has an important role to play in building capacity by training the next generation of people to think critically about these issues. It is also a place where various disciplines can come together to be able to respond to these incredibly challenging questions with the very best evidence and data possible,” she said.

Lauren Wolkoff (G’13)

GUMC Communications