To Reduce Health Disparities, First Acknowledge Past Research Wrongs

Posted in GUMC Stories

NOVEMBER 7, 2014—With the goals of righting past wrongs and building trust between researchers and racially and ethnically diverse communities, Georgetown University Medical Center (GUMC) has developed a novel pilot study consisting of a series of community forums called “Truth and Reconciliation.”

Led by Tawara Goode, MA, assistant professor and director of the National Center for Cultural Competence (NCCC) at Georgetown’s Center for Child and Human Development, the study is funded by a Reflective Engagement in the Public Interest grant out of the Office of the President at Georgetown. It was conducted with support from the Georgetown-Howard Universities Center for Clinical and Translational Science (GHUCCTS), including Mary Ann Dutton, PhD, associate professor of psychiatry at GUMC.

In four three-hour Truth and Reconciliation community forums held in downtown D.C. this past winter and spring, Goode and her collaborators acknowledged past wrongs committed in research between 1900-1995, issued an apology on behalf of the “research community” as a whole, and detailed participant rights and protections now embedded in research.

Removing Barriers

The project responds to a deeply rooted challenge for the research community—low participation in research studies by members of racially and ethnically diverse communities. While researchers agree that there are disparities in the health and well being of patients from specific racial and ethnic groups throughout the country—and D.C. is not an exception—academic and research institutions have often struggled to attract these populations to participate in research.

A complex set of factors affect the willingness of some groups to participate in research, most notably historical distrust of medical research institutions and reluctance to be “experimented on.” There is a general lack of knowledge about what clinical trials and studies are designed to do, including all the protections that have been put in place to safeguard research participants, according to Goode.

“Many individuals affected by health disparities are unaware that studies are conducted in partnership with their communities and that they can be meaningfully engaged in research in a role other than as a subject,” Goode says.

Through this project, researchers sought to determine if barriers to participation in research can be reduced by community forums designed to acknowledge past injustices, foster reconciliation between research institutions and the communities that have been victimized, increase awareness of research safeguards, and ultimately increase participation in research that can aid in reducing health disparities.

Lessons from the Past

Reconciliation is an important concept in societies that have experienced deep inequities and injustices, and where the communal trauma of these injustices has seldom been acknowledged. It is a process that has been employed in international and domestic conflicts across the world—and has been recently applied in North America to human service systems including the field of medicine.

The forums resonated deeply with participants who were not as familiar with past research injustices.

“I was absolutely shocked — just blown away,” says Allyson Coleman, one of the 29 Truth and Reconciliation participants who viewed a slide show detailing examples of harms conducted in the U.S. from 1900-1995.

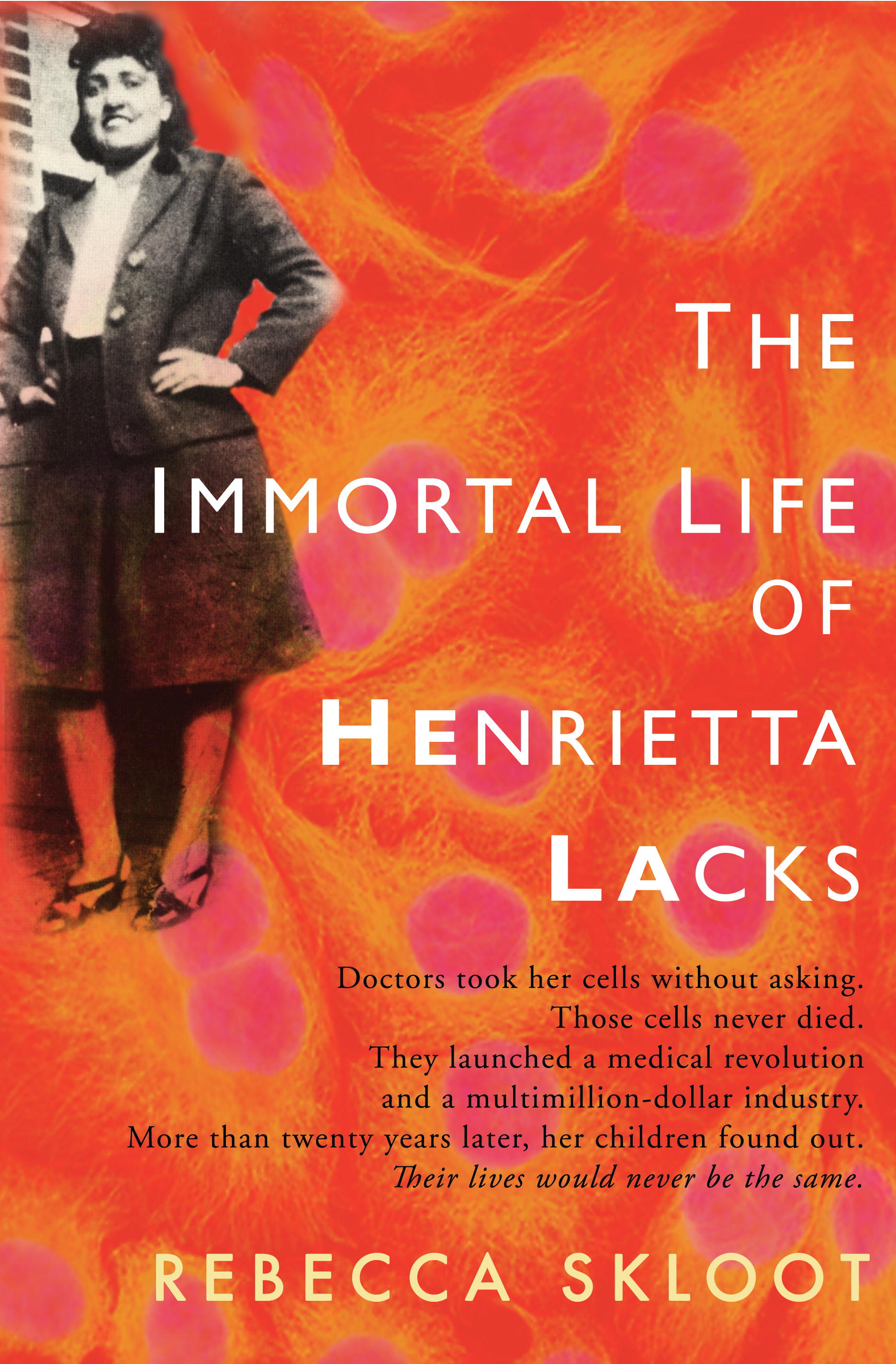

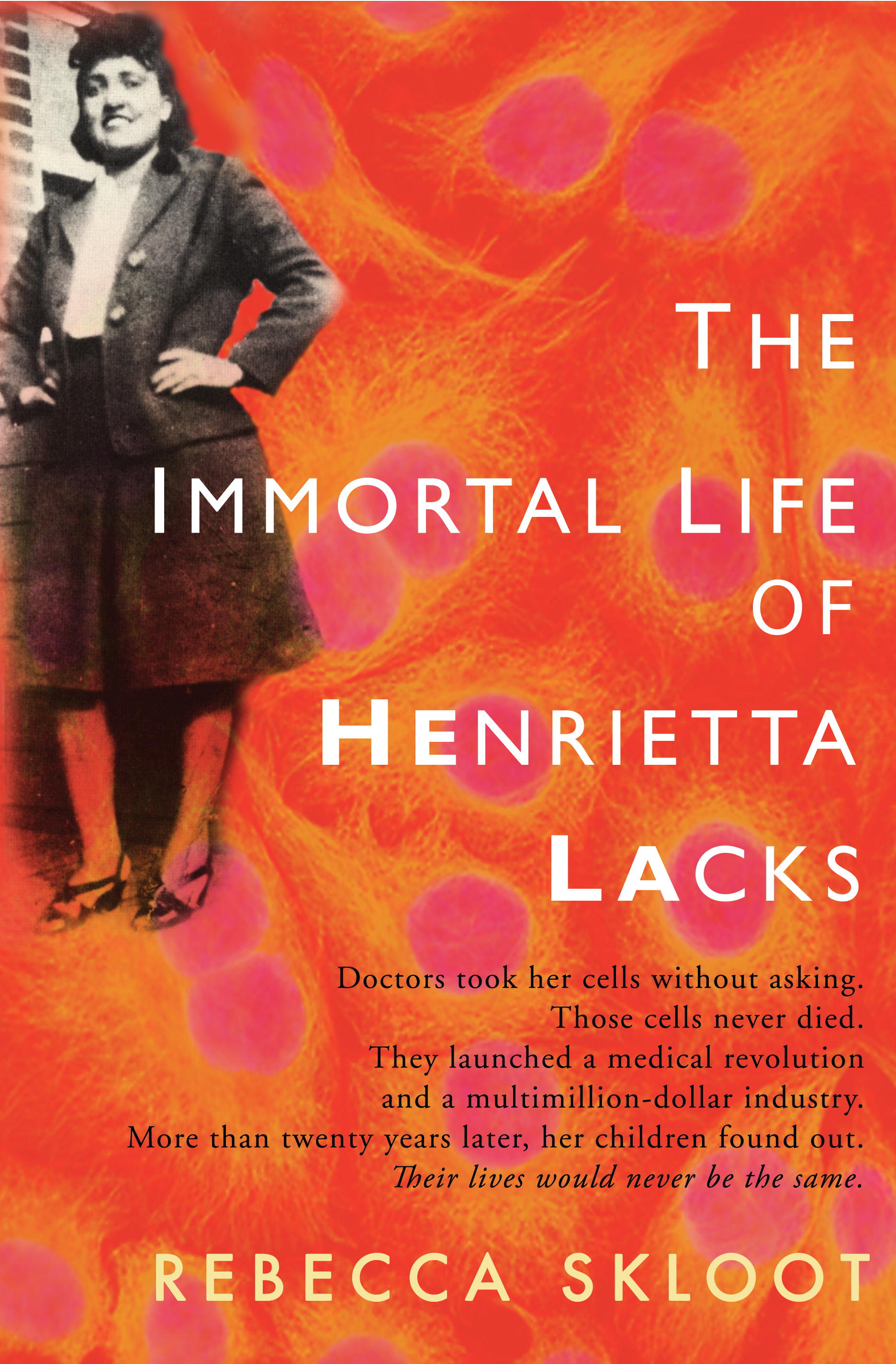

Coleman, who works in the department of community and health services for the city of Alexandria, says she knew about the

40-year experiment withholding syphilis treatment for affected black men at the Tuskegee Institute, and was aware of use of a black woman’s tumor tissue for laboratory experiments without her approval or that of her family. These “immortal HeLa” cells—named for the woman Henrietta Lacks from whom the cells were taken—have been used worldwide for decades.

40-year experiment withholding syphilis treatment for affected black men at the Tuskegee Institute, and was aware of use of a black woman’s tumor tissue for laboratory experiments without her approval or that of her family. These “immortal HeLa” cells—named for the woman Henrietta Lacks from whom the cells were taken—have been used worldwide for decades.

But Coleman did not realize the extent of the eugenics movement, wherein women with various types of disabilities and from specific racial and ethnic groups were sterilized without their knowledge in 33 states.

Nor did she know that children with intellectual disabilities were fed oatmeal with radioactive particles or that 90 poor, black patients with inoperable tumors were exposed to secret and classified radiation experiments.

Even as recently as the 1990s, a study was conducted in Baltimore’s inner city to test how well different abatement strategies worked to reduce lead in the housing stock—and the overall impact on lead levels in the blood of the children residing in these homes. The study was suspended after several parents alleged their healthy children had been harmed and filed lawsuits for negligence and failure to warn of potential irreversible harm caused by lead exposure.

Coleman found these disclosures incredibly powerful, and even more so because they were accompanied by an apology from the scientific community. The apology was recorded by Goode’s team at the NCCC and delivered as part of the Truth and Reconciliation process.

This approach is “a very effective strategy to change people’s minds about participating in research that may ultimately help the community,” Coleman says. “I understand the bigger picture now. We should all now move forward.”

An Airing of Grievances

Participant Ron Smith was also stunned by the breadth and depth of the community forums, saying that Goode took a “very sensitive approach to the history while not cutting any corners.”

“The opportunity Georgetown has to bring this issue into the forefront is incredible, and they are doing it right,” says Smith, a recent graduate from Catholic University who works for Andromeda Transcultural Health Care as a substance abuse counselor.

Smith, who also volunteers with the DC chapter of TASH, an international disability rights organization, believes Truth and Reconciliation workshops could be very well received in minority churches and community halls because they allow a full airing of grievances and turn negative emotions, such as anger, into positive perceptions and actions.

Changing Hearts and Minds

Analysis of the post-workshop findings is ongoing, Goode says. But larger studies will be needed to see if hearts and minds regarding participation in medical research can truly change from participation in the Truth and Reconciliation project, Goode says.

“If we can have an impact, I would hope that this model will be used by other academic institutions that are focusing on health disparities research in their own diverse communities,” Goode says. “We really need to build these community partnerships and to acknowledge, quite frankly, our past wrongs in order to be able to move into the future.”

GHUCCTS is a collaborative research center formed by Georgetown and Howard universities, MedStar Health Research Institute, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, and the Washington DC VA Medical Center. It is a member of the CTSA (Clinical Translational Science Award) Consortium, a collaboration of 62 institutions nationwide funded by a highly competitive, $38-million grant from the National Institutes of Health.

By Renee Twombly

GUMC Communications