How Medical Students Continued Community-Based Learning During the Pandemic

Posted in GUMC Stories | Tagged community outreach, community-based learning, medical education, School of Medicine, service to others

(July 23, 2021) — As the organizers of community-based learning (CBL) for Georgetown medical students, Kim Bullock, MD, and Donna Cameron, PhD, MPH, have built relationships with the leaders of more than 20 community sites in the Washington, D.C., area that serve vulnerable populations, including persons with disabilities, older adults and persons in supportive housing.

Those relationships helped ensure that medical students could continue CBL when classes were moved online due to the pandemic. “Dr. Cameron and I did a lot of intense partnership work, canvassing the community to see who could feel comfortable translating their work to do online,” said Bullock, community health division director and associate professor of family medicine.

In addition to the flexibility of those community partners, the hard work of the team at Georgetown made virtual CBL a positive experience. “You can’t do it without support and buy-in from the top,” said Cameron, professor of family medicine and former CBL director. “Support from staff, buy-in from the top and trust from the partners. That’s the secret sauce of this course.”

CBL at Georgetown

A required part of preclinical education, first-year medical students begin CBL in August by choosing their sites. Starting in January, students have seven scheduled sessions with their sites. Throughout the course, students write brief essays reflecting on their experiences.

After the scheduled sessions, students work in groups to write their final essays, then create brief videos about their sites to help the next class of students choose their CBL sites.

For some students, CBL is the beginning of their engagement with a patient population. “A few students have stayed engaged from year one to year four, and their ISP [independent scholarly project] was the result of all of the work that they’ve done throughout those four years,” Bullock said.

For example, Bullock said, one student researched why patients opted out of HIV testing at Providence Hospital and how health care workers could encourage more patients to get tested. “He had a publishable deliverable at the end of his time period,” she said.

“Some stay in touch with organizations for coming years,” said Margaret Eshleman, M.Ed., education coordinator for CBL and the population health scholar track in the family medicine department. “It becomes a passion project, and they make these connections.”

Preparing for Virtual CBL

In the summer of 2020, it was unclear whether CBL would take place in-person, online or some combination of both formats. Bullock taught her CBL class online, while Cameron took advantage of opportunities from Georgetown’s Center for New Designs in Learning and Scholarship (CNDLS) to prepare to lead in a virtual learning environment.

“I wouldn’t call myself a techie, but since we had to become techies, I tried to figure out what do techies do,” Cameron said. “That was the very first thing.”

Eshleman, Bullock and Cameron stayed in constant communication with community partners to see if and how they would be able to accommodate students, offering ideas for activities that could take place online. When they learned at the end of July that the class would be online only, they had about two weeks to finalize plans for about 200 students and more than 26 sites.

“We thought it would be hybrid, but then it was virtual only, so we lost a few sites, but some sites stepped up,” Eshleman said. “That was completely understandable. We’re in touch with a few of them now to see if we can re-establish that relationship as we are shifting to in-person again.”

Pleasant Surprises

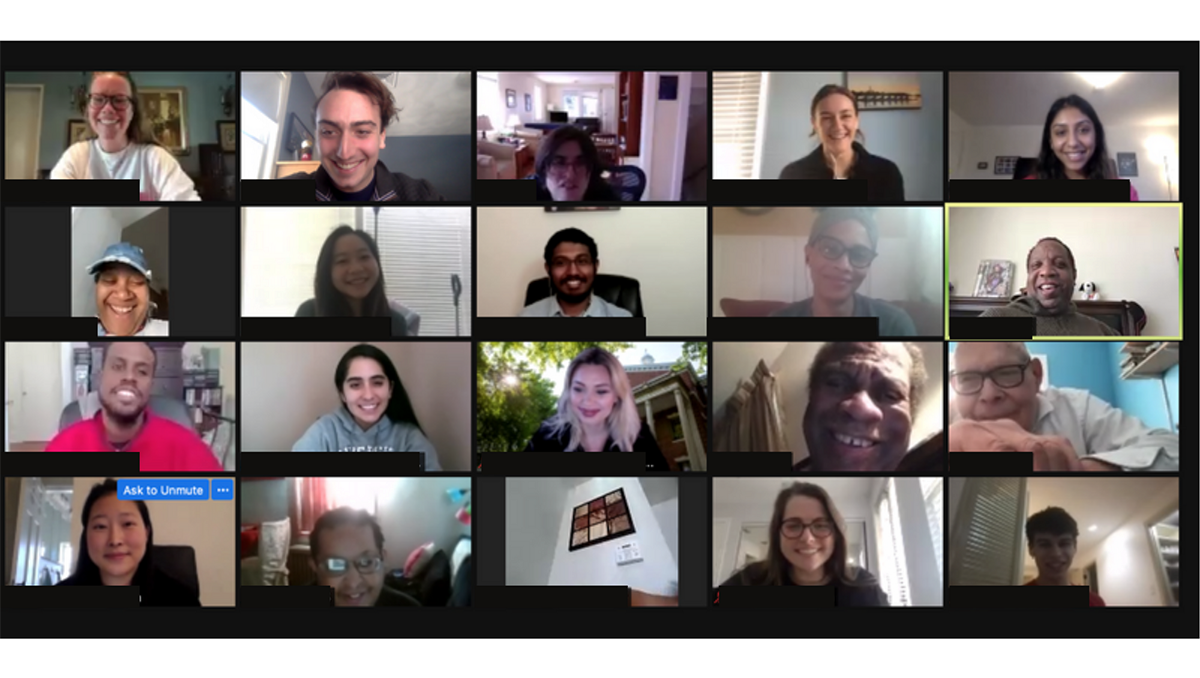

Typically, first-year medical students attend a CBL fair where they connect with second-year students to discuss their experiences and ask questions. For 2020, first-year students watched the videos made by the second-years before participating in a virtual fair.

There were several advantages to holding the fair online. Because they watched the videos ahead of time, first-year students didn’t repeat the same questions in the information sessions, giving the second-year students more time to speak about their experiences and answer questions. It also allowed community partners to participate. “It was shown in the reflections this year that connecting with the community partners at the fair helped them choose that site,” Eshleman said.

Virtual CBL also enabled new faculty site leaders to get involved. “This year, I think, partly because of the virtual environment, we were able to recruit two faculty members from [MedStar] Franklin Square because they could do it virtually,” Cameron said. “They could lead online so that was a new finding. I’d never had that experience before.”

Making It Work

Some sites comfortably transitioned to the virtual setting, including one where medical students tutored younger children. Other sites had technical challenges, including limited computer availability and unreliable internet access. However, the medical students dedicated themselves to making the most of their opportunities.

“They love a challenge,” Cameron said. “I think they took it as a challenge. And the goal was, let’s make the best of this bad situation, and I think most of them did.”

At a resource center for women and children experiencing domestic violence, Bullock said, it was difficult for clients to engage with the medical students online, so the students focused on learning what they could from the staff.

“They got to hear from the staff about the stress and the challenges, about things that they, as medical students, should know about that population,” Bullock said. “They learned things that they weren’t expecting to learn and they also thought creatively about ways they could improve this for next year.”

After taking a year off from being a CBL site before the pandemic, one site serving those facing food insecurity returned for 2021, giving students the opportunity to take clients’ life histories. At another site, a church where many of the parishioners are older adults, the medical students organized a virtual health fair.

“It was nice that everybody was in the same boat,” Eshleman said. “We were all learning together, and the students were trying to figure it out too, but I think the community partners really stepped up.”

In a pandemic-specific CBL experience, one group of students organized listening sessions to learn from adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities who advocate for their community about their experiences using technology to overcome isolation and build community during the pandemic.

“The students came in not appreciating the fact that individuals with disabilities could use the virtual platforms in the same way to the same degree of sophistication as everyone else and they demonstrated that they were able to, and that became their main way of communicating and keeping relationships going,” Bullock said. “I think that was a real learning experience with the students.”

‘Flexibility is Our Best Friend’

Organizing CBL during a pandemic showed Eshleman the importance of contingency planning. “You don’t want to have to make a backup plan, but at least we know that we can be virtual,” she said. “Flexibility is our best friend.”

Bullock expressed pride in the medical students’ flexibility. “They have to be creative, and where it’s not working, come up with alternatives,” she said. “And if those alternatives don’t work, keep at it until there’s a breakthrough.”

Some of the changes made to accommodate virtual learning, such as the virtual site selection fair, will persist even as students return for in-person classes. During virtual learning, students, faculty, staff and community members made a point of checking in on each other often, and Cameron expressed hope that everyone involved will continue that practice.

“One thing I want to keep doing, because the virtual environment showed the value of it, is being intentional about building community among the students and faculty and partners, and keeping in touch more,” she said. “I just think that we don’t do enough of that. We didn’t do enough of that until we had to. And I think that made a difference.”

Kat Zambon

GUMC Communications