GUMC Expert Leads Charge for Gender Equity in Preclinical Research

Posted in GUMC Stories

JUNE 20, 2014—The issue of male sex bias has long plagued laboratory research —due to factors such as convenience, cost and inertia, a majority of preclinical studies are conducted in male cells and animals, leaving females largely out of the equation.

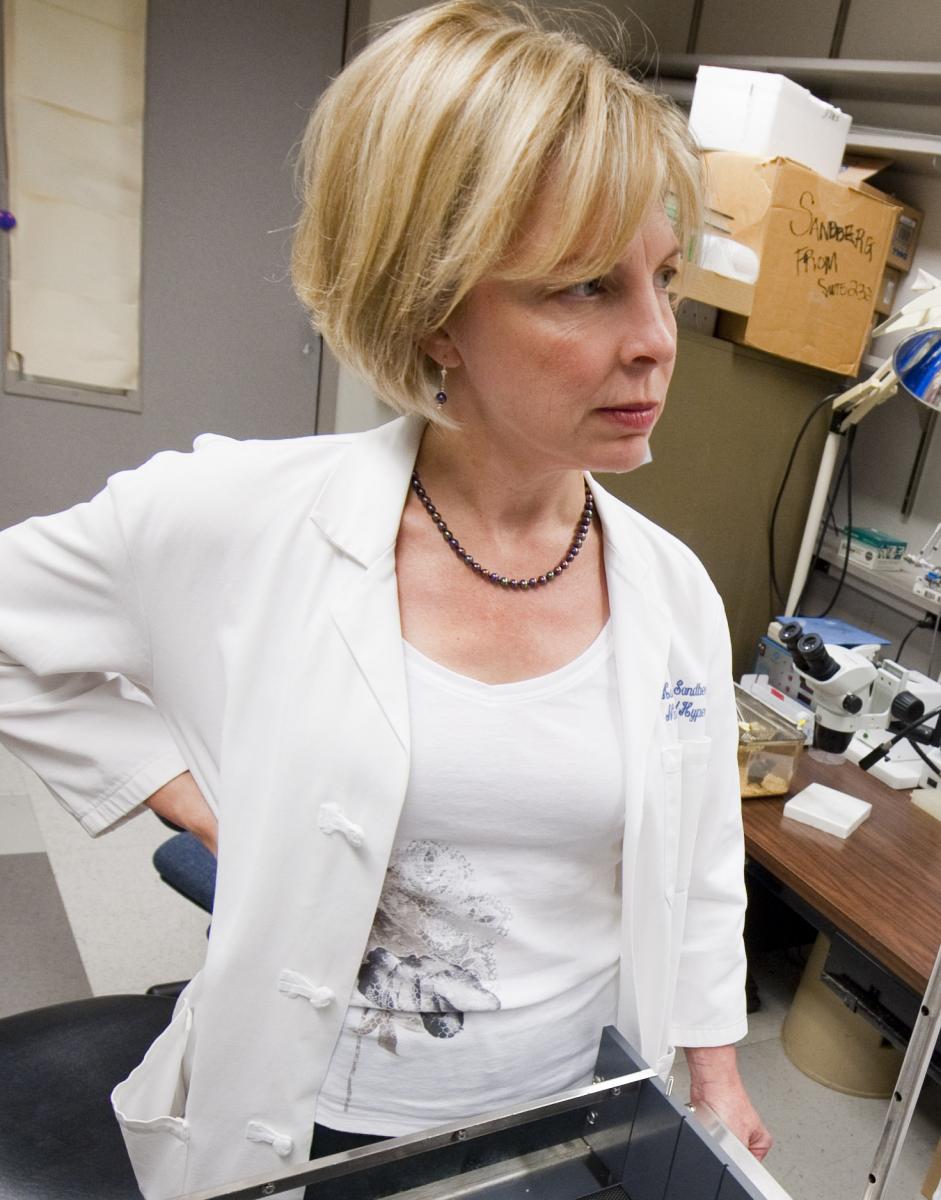

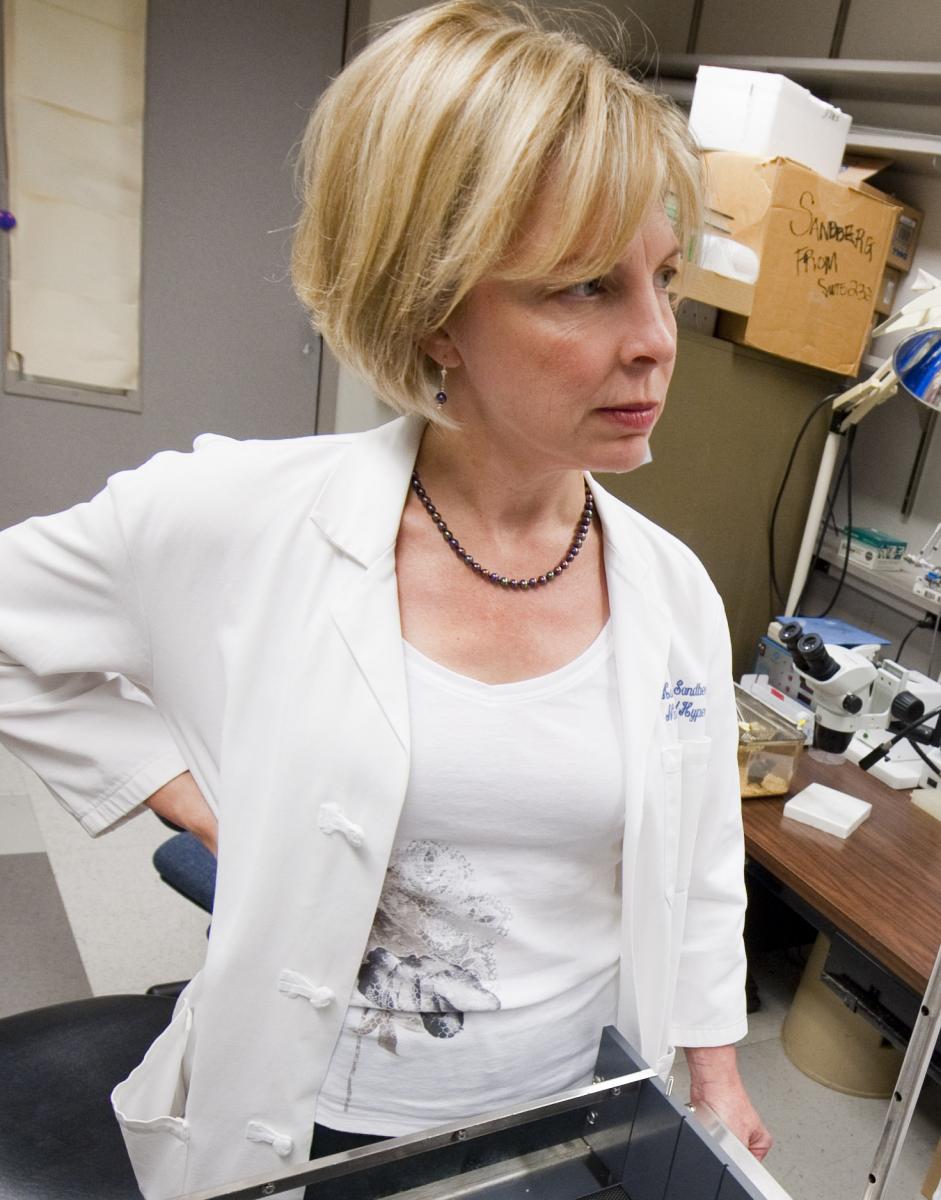

Yet, with the help of the expertise of Georgetown University Medical Center researcher Kathryn Sandberg, PhD, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) is poised to implement reforms that aim to address the underrepresentation of female cells and animals in preclinical research.

As director of GUMC’s Center for the Study of Sex Differences in Health, Aging and Disease, Sandberg has long advocated for sex equality in preclinical as well as clinical research. She stresses that female as well as male cells and animals need to be studied to understand how diseases, and the drugs that treat them, differ between the sexes. Her own research, for example, has shown that the basic mechanisms underlying hypertension are not identical in males and females. Thus, new antihypertensive medicines developed from preclinical research done only in male cells and animals could lead to drugs that are less effective or possibly even have more negative side effects in women.

While Sandberg’s leadership on this issue is helping pave the way at Georgetown, nationwide, it is a different story. A study published in 2011 in Neuroscience Biobehavioral Review estimated that male-only animal models continued to dominate basic research — the ratio of male-based studies to female is four to one across multiple disciplines, Sandberg says.

“Even when both sexes are included, most researchers don’t analyze their data by sex in a scientifically sound manner,” she says.

“Sex differences are evident in physiology and even down to the level of cell biochemistry and genes,” she adds. “Men and women are not the same, but when they are treated that way, medicine suffers. The Food and Drug Administration has withdrawn several drugs from the market, and therapeutic doses have been changed, because of the after-market discovery of serious toxic side effects in women.”

Appealing to Congress

Sandberg and Scott Fleming, associate vice president for federal relations at Georgetown, visited the offices of two U.S. Congress members last year — Nita M. Lowey (D- N.Y.) and Rosa DeLauro (D-Conn.) — to make the case for gender equality in publicly funded basic research. In 1993, Lowey and DeLauro were instrumental in passing the NIH Revitalization Act, requiring the NIH to include women in federally funded phase 3 clinical trials.

Following those meetings, Lowey and DeLauro penned a letter earlier this year to NIH Director Francis Collins, MD, PhD, stating “the lack of inclusion of female animal models in basic research undermines the credibility of research …”

Collins and Janine Clayton, MD, director of NIH’s Office of Research on Women’s Health, took the legislators’ letter seriously. In a May 14 commentary in the journal Nature, they vowed to balance male and female cells and animals used in preclinical studies in all future application for research funds.

Listing a number of conditions now known to differ between the sexes — multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, schizophrenia, stroke, drug addiction, obesity and metabolic disorders, they noted that “sex may well contribute to the troubling rise of irreproducibility in preclinical biomedical research.”

New policies will be rolled out in phases beginning in October 2014, they wrote.

A Title IX Approach

Sandberg is heartened that the letter from Lowey and DeLauro seems to have had an impact.

“It could be the trigger that sets in motion some equity in basic biomedical research,” she says.

Yet she worries that the policies that might emerge may not spur meaningful change, and that investigators will find a way around them.

“They may say they will study both sexes, but then, when the research is underway, they might measure one parameter, say there is no difference in the sexes, and proceed using the male models they have in their labs.”

So Sandberg decided that when it comes to public funds for basic biomedical research, a “Title IX approach is needed” — referring to the 1972 legislation enacted to protect against gender discrimination in federally funded educational programs.

Rather than attempting to achieve a male/female balance in every preclinical study, she says, NIH could ensure the overall research budget is spent equably in aggregate on male and female cells and animal models of disease.

“I call this a Title IX position,” she says. “I propose that the proportion of male and female models used to investigate specific diseases should reflect the disease prevalence in the general population.”

Sandberg and colleagues outlined this position in a June commentary called “Point/Counterpoint: Sex and Basic Science. A Title IX position” in the American Journal of Physiology – Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology.

Georgetown Forging Ahead

GUMC leaders praise Sandberg’s pioneering efforts, while recognizing the significant challenges ahead.

“There is no question there is sex bias in preclinical studies,” says Joseph Verbalis, MD, chief of endocrinology and metabolism at GUMC and co-director of the Georgetown-Howard Universities Center for Clinical and Translational Science.

“Changes to achieve a better balance in studies of both females and males may be disruptive and challenging in the short-run, but will be tolerable given the important long-term benefits of much richer information about how males and females respond to disease processes and treatments, which we know can be very different,” Verbalis says.

Just as researchers have worked hard to include more minorities and females in clinical research over the past few decades, a similar transition in preclinical research “should have been done nationwide years ago,” says Robert Clarke, PhD, GUMC’s dean for research and a breast cancer investigator.

“We have had a very good start at Georgetown on changing our strategy based on Dr. Sandberg’s work, and we are committed to going all the way to provide the best study possible of both male and female disease.”

By Renee Twombly

GUMC Communications