Title:In Perfect Harmony

Medical student arts collective fosters healing

Music as Medicine

Medical student musicians took white coats off and put guitar straps on for hospital rounds with a twist. Georgetown’s new Arts & Medicine student collective is on a mission to enhance patient care and medical education through the arts and creative programming.

The laughter started rippling through the Proctor- Harvey Amphitheater soon after Nick Stukel (M’18) sang the first verse of his song, “Doctor,” but it really exploded when he reached the chorus.

“I want to be a doctor, if I can make it through this thing,” he belted out in a pitch-perfect voice from behind a piano he was playing. “Will it ever be over? So many highs but so much strain. Got a long list of mnemonics, no more room in my brain. Time to make some more space baby, and play the game.”

Stukel wrote the tune, set to Taylor Swift’s “Blank Space,” in less than 24 hours, following a particularly stressful few weeks (aren’t they all in medical school?) of interviewing for residencies. Like the other musical numbers, dance exhibitions, poetry and essay readings that highlighted the Arts & Medicine student group’s “What Makes You… More Than Medicine?” night of performance, his rendition was exceptional not only in its composition and execution, but also for the sheer and obvious joy it brought the audience and other participants.

The mid-January show was the perfect example of why the dozens of students who take part in one of Arts and Medicine’s many events say the group has changed their medical school experience—and made them better doctors-to-be.

“I find it interesting when people think there’s a dichotomy between art and medicine,” says Christine Papastamelos (M’19), one of the group’s cofounders. “I’ve always found them to be supplemental to one another. I was an art history major in college, and people would be like, ‘That’s weird, you’re doing pre-med.’ But engaging yourself in art is a way to understand other people and to share something about yourself. I think a lot of it is about listening, and human connectedness.”

Papastamelos, John Guzzi (M’19), and Dylan Conroy (M’19) started Arts & Medicine in 2015. As an undergraduate at Boston College, Guzzi played in a rock band and was president of a musician collective that performed for kids at a children’s hospital.

“That’s what got me turned onto medicine in the first place,” he says. “I couldn’t imagine not doing that kind of work.” So when he got to Georgetown, he and his two new friends founded what was originally called Music & Medicine. Then, as they still do now, they played for children in the pediatric ward of MedStar Georgetown University Hospital.

Equipped with guitars plus tambourines and shakers for the kids to use, a handful of med students performs on weekends for the patients and their families and friends. Their catalogue includes Disney songs like “Let It Go” from the movie Frozen, a Justin Timberlake tune or two, and classics that older people enjoy. For the little ones, “Old MacDonald” and “Wheels on the Bus” are surefire winners.

“If you talk to anyone in the club, playing for the kids is probably our favorite thing we do in med school,” says Conroy, a guitar player (and singer when he “has to be”). “Not only to see the kids light up, but it also takes a little bit of stress away from the families. I can only imagine how terrible it is to have your 2- or 3-year-old kid in the hospital.”

Sadly, Claire Hughes knows that reality all too well. Her 12-year-old son Will was diagnosed with brain cancer two years ago. He was in the hospital for more than a week when he had his first surgery in January 2016.

“It was such a nice break for him to be distracted by all these wonderful students who sang,” she says. “He smiled and so did everybody who was with him. You go from crying to smiling—the music just brings you joy and happiness and lifts your spirits. That’s why I fell in love with the program.”

Yet listen to the students who perform at the hospital describe the experience and it isn’t clear who benefits from the visits the most.

“It helps you look at people as more than just numbers, and it really helps you connect with their stories,” says Marilyn McGowan, co-president of Arts & Medicine. “Looking at medicine just as a science makes you think in a very binary and formulaic way. Having that arts component helps us remember that no two people and no two patients are the same.”

“Difficult classwork is one thing, but what you really lack in med school, especially in the first two years, is face-to-face interaction with the people you get to serve,” Papastamelos says. “A lot of time being a student can be solitary—you’ve got to learn your information. But when we take a break and go see these kids who are really sick or have just had a major surgery, it’s gratifying to realize that this is the profession you’re growing into.”

The School of Medicine and Medical Center community gathered in January for a talent showcase called “What Makes You…More Than Medicine?” inspired by the Jesuit concept of magis (more than).

Increasingly, medical institutions across the country are offering programs to support arts-based healing, despite a continuing shortage of evidence-based research on the impact of the arts on health care providers and patients.

One reason for the lack of data, says Dr. Caroline Wellbery, Arts & Medicine’s faculty advisor, is because designing studies on the subject is exceedingly difficult.

“It’s not like taking a pill,” she says. “There are so many things that impact patient care. But I think arts are integral to what humans need. The arts in medicine have multiple purposes, one of which is entertainment and pleasure. But also it’s an avenue toward reflection. Performance makes you think about things a little more deeply. It’s healing for students to be engaged in something like this, where they can turn off part of their brain and just be in the moment. We don’t really understand why creativity is so healing. But it’s restorative, like sleep, and nobody understands that either.”

On a rainy winter Saturday, a group of six Arts & Medicine musicians made their way to the post-op unit at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital. Patients were asked if they wanted a visit from the troupe, to which Kelley Williams enthusiastically responded “Yes, please!”

As medical student guitarists and vocalists entered the room, and her face lit up with joy. The musicians squeezed together to make a little more space as they keyboardist rolled his instrument in on a hospital over-bed table. As they began an achingly beautiful rendition of “Wagon Wheel,” the energy transformed the room and those in and around it. Busy staff walking by the open door couldn’t help but smile, and a patient walking the hall with his two family members slowed to linger and enjoy the melodious voices. A group of recent Nursing & Health Studies graduates gathered outside the room, too, soaking in the sounds and smiling when they learned the musicians were Georgetown med students.

Between songs, the patient shared that she is an elementary orchestra director, and plays the viola and violin. She closed her eyes and took a deep breath. She opened her eyes and looked around slowly at each musician. “What you’re doing is so important,” Williams says softly, shaking her head. “You never know who you touch. You made my day.”

Shortly after its formation, Arts & Medicine broadened its focus from music to include the written and visual arts.

“I think one reason our club took off so quickly is because there’s just something inherent about art being an avenue to open yourself up to other people,” Papastamelos says. “I think that really draws our class together; they experience that connectedness. It’s really pretty infectious, although infectious is probably a bad word in medical school. Infectious in a good way.”

Today, many poems, essays, photos, short stories, and paintings are featured in Scope, the group’s creative journal. It offers students who are more introverted a forum to share their work and a way to be involved with the organization, without having the knee-knocking experience of standing before an audience to perform.

The second volume, released early in 2018, includes a watercolor of children on a beach (“Summer Days” by Katherine Wickholm (M’19)), a painting of Med- Dent by Karen Schirm (M’20), and an untitled, abstract oil painting by Cameron Zachary (M’21). There also are plenty of stunning photographs, including a dramatic sunset at Yosemite National Park by William Ferris (M’20).

In the issue, Lauren Klingman (M’19) has a series of pencil sketches entitled “A Physician’s Exam: Inspection, Auscultation, and Palpation.” At the event in January, she dealt with personal identity in her reflection, “From Acting to Medicine,” which took the audience through 20 years of her life as an actor.

“It’s hard for me to believe that it’s been almost seven years since I decided to officially call it quits on theater and go into medicine,” she said. “It was the last time I called myself a professional actor or artist. I’m still struggling to redefine myself and questioning if it is alright to feel like an artist. I’m still trying to find a way to blend both.

“It’s a part of my identity that often doesn’t get brought up,” she said after her reading. “You get stuck in this ‘cookie cutter’ role of a medical student. It’s nice to let people know you have another identity.”

Perhaps that’s why Stukel’s song was such a hit. As medical students, most in the audience could relate to the lyrics of “Doctor,” which detail the specific trials and tribulations of each of the four years of medical school. But they also appreciated their classmate’s ability and willingness to perform.

“For a lot of medical students and physicians, some form of involvement in the arts, whether it’s music or writing, allows for a creative release of a lot of the tension and frustration that builds up through difficult patient situations,” says Stukel, who keeps an 88-key keyboard in his room. “By tapping into that right brain side, the more creative aspect of ourselves, we’re able to be better communicators, maybe notice more subtle things with patients and their demeanors, and relate to them in a little broader way than just the clinical context.”

A native of South Dakota and graduate of Creighton University in Nebraska, he was a member of a Christian rock band named Godstruck that played for audiences of 50 to a few thousand people throughout the Midwest. The reception from some of those crowds might have been louder, but few could possibly have been more enthusiastic than the one at the January event, which gave him a rapturous ovation after the final verse.

“Feels like forever, that med school’s way too hard,” he sang. “And even when it’s over, that I won’t know enough. Got a long list of case studies, they’re driving me insane. Buckle down, let’s do this, get that M-D in my name.”

Giuliana Cortese of GUMC Communications contributed to this story.

Operating theater takes center stage at the university’s annual Heart of the Harvey dramatic arts festival.

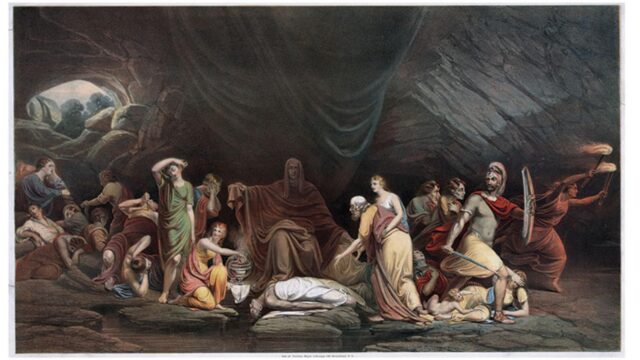

Above: Rembrandt Peale’s The Court of Death, 1820 The brain—a magnificent organ that enables human expression— forms the most elaborate electrical network in the human body. At the…

Sylvia Morris (M'98)…