Title:Under Study

Giving back through clinical trials

Kara-Grace Leventhal forged a connection to the Georgetown medical community years prior to being admitted to the 2018 School of Medicine class.

“I was born at Georgetown Hospital, and some of my earliest memories are of appointments with my pediatrician at Georgetown,” says Leventhal. “I had a number of food allergies that my mother was struggling to diagnose and respond to, and after several doctors downplayed the condition and her instincts, my Georgetown pediatrician empowered her by saying, ‘You’re the mother. You know her best. What do you think?'”

Leventhal says this memorable interchange exemplifies a common theme and mindset that runs through the Georgetown medical community: Yes, we know the science—but we also need and value the patient’s perspective.

A few years later, when Leventhal was 9, her mother was diagnosed with an aggressive form of breast cancer, and joined a clinical trial offered at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Through close monitoring and evaluation while on the trial, her medical team caught a secondary cancer very early on which was successfully treated. Leventhal credits the trial with saving her mom’s life.

After that experience, Leventhal knew she wanted to work in health care. She earned her undergraduate degree in psychology and took a job at Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center as a research assistant, enrolling patients in clinical trials and coordinating genetic testing for breast cancer risk.

In that position she had a close-up look at the patient experience during cancer treatment. This perspective solidified her interest in becoming a doctor, in order to better influence treatment decisions and advocate for patients.

Little did she know that just two short years into her research assistant position, the tables would turn.

From researcher to patient

After being immersed in the clinical study of genetic mutations that make women highly susceptible to breast cancer (mutations of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes), Leventhal learned what she had begun to suspect: she was a carrier of this genetic mutation. It presents a 55-65% lifetime risk of developing breast cancer, in addition to increasing her chance for other cancers.

“It seemed like a matter of when, and not if,” says Leventhal.

In response to these grim cancer risk statistics, a woman who carries this genetic mutation encounters a host of overwhelming, life-altering treatment decisions: chemopreventative drugs that affect the ability to start a family; extensive and cumbersome surgeries that remove and reconstruct the breast prior to diagnosis; or the wait-and-see approach that focuses on diligent screening, to name a few.

Each choice has its pros and cons, affecting the woman and her family in a myriad of ways, and the cost/benefit analysis process shouldn’t be faced alone, says Leventhal.

“I received genetic counseling from my colleague at Lombardi Cancer Center and it was immensely helpful,” says Leventhal. “Both my husband and I met with her for an hour and a half to discuss future plans and treatment implications.” The counselor also connected her to a support group for women in similar circumstances.

Leventhal opted to be rigorous in her screening, but to also do what she could for future women facing such a diagnosis. She enrolled in a clinical trial exploring the effect of Vitamin D on those at high risk for breast cancer.

The decision for her was an easy one. “I can’t control whether or not I have this mutation, whether it’s in my family, but I can contribute to better treatment and outcomes for other women.”

Leventhal credits the nurse coordinator who oversaw the clinical trial as incredibly helpful as she struggled with confusing consent forms and navigated through additional biopsies and mammograms that came with enrollment in the trial. After one year of the experimental treatment, Leventhal went back for an additional biopsy and had developed a hematoma. Her doctor immediately removed her from the trial out of an abundance of caution.

Even though she was unable to complete the trial, she would wholeheartedly recommend that others seek out these trials and participate in them.

“The statistic of less than 10 percent of cancer patients enrolling in clinical trials should horrify everyone. You’re going to benefit society at large so much by signing up for a trial and giving back,” says Leventhal.

Clinical trials in the U.S.—a lost opportunity?

Medical advances depend on successful clinical research. More than 200,000 active clinical trials are underway in the United States today, according to the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

However, the participation rate for cancer patients is just 3%. Additionally, almost 40% of clinical trials in the United States fail to enroll the minimum number of patients needed to complete the study, and end up closing before they are completed.

Why are enrollments so low? NIH studies on the issue cite a number of different reasons that patients elect not to participate in clinical trials, including fear of a reduced quality of life, concern about receiving a placebo, potential side effects, and concern that the experimental drug might not be the best option. The single largest determining factor was physician influence.

Filipa Lynce, associate professor and medical oncologist at Lombardi, notes another reason that the numbers are low: strict participation requirements eliminate some willing patients. Factors that take potential participants off the list include the presence of an additional disease or health condition, lab results that are deemed unacceptable, and patients who are on specific medications for another condition.

Low participation rates also impact drug development, says Lynce.

“Because so few patients participate in clinical trials, we are delaying and compromising the development of new drugs that could save the lives of future patients. Our newest and best drugs recently approved for the treatment of breast cancer were developed through clinical trials which required thousands of women to enroll in order to show success,” says Lynce.

She also sees practical roadblocks to enrolling a broad spectrum of potential participants. “Many trials have informed consent forms that are more than 20 pages long and may not be easy to read or understand. Other trials only have these forms available in English. I think there is a lot of work to do on the part of medical institutions to get clinical trial enrollments to be more representative of the general population, including minorities,” says Lynce.

‘A gift I can never repay’

Leventhal is now a second-year medical student at Georgetown. One of her recent classes focused on cancer and provided statistics on multiple myeloma, a cancer of blood plasma cells. She learned that the life expectancy from time of diagnosis to death for the disease averaged three years.

Two weeks after that class, her father was diagnosed with multiple myeloma. Much to her surprise, when meeting with his oncology team she was told that the survival statistics had recently improved dramatically: the life expectancy with current treatments had risen to seven to 10 years, on average. The longer life expectancy for these patients, and her father, can be directly attributed to clinical trials.

“Patients facing this disease 10 to 15 years ago were willing to enroll in clinical trials to study it,” notes Leventhal. “Thanks to those individuals, patients today are living three times as long. Participating in clinical trials helps future patients get back years of their lives. It’s a gift I can never repay.”

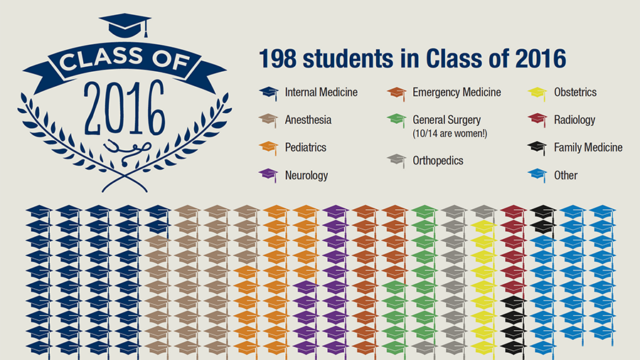

Match Day is a pivotal day in the life of graduating medical students.

Through a series of key building enhancements and accessibility projects, the proposed expansion addresses the urgent age, capacity, and technology issues of the hospital today.

The Huntington Disease Care, Education & Research Center at Georgetown has been designated as a Center of Excellence by the Huntington's Disease Society of America.